Police drones are becoming more and more commonly utilized by law enforcement agencies across the world. As of 2017 there were 347 American police departments using unmanned aerial technology. This number represents a 518% increase over a two year time period. Police are quickly catching on to how drone technology can help make police work easier and safer.

One of the ways drones are being utilized is in surveillance. Drones have the ability to reach vantage points that would either be impossible for an officer to reach, or expose the officer to danger. A drone can get to a great vantage point without having to compromise the safety of an officer. This ability is especially useful in an active shooter scenario, where the lives of the law enforcement officers are on the line.

One of the ways drones are being utilized is in surveillance. Drones have the ability to reach vantage points that would either be impossible for an officer to reach, or expose the officer to danger. A drone can get to a great vantage point without having to compromise the safety of an officer. This ability is especially useful in an active shooter scenario, where the lives of the law enforcement officers are on the line.

Being able to view and assess threats remotely not only minimizes risk, but allows police to formulate a strategy. Drones can also minimize risk to bystanders. If a suspect were to commit a crime then run into a crowd of people, a drone would be able to track the suspect through the crowd rather than have officers run after and risk harm to an innocent bystander. The video footage from the droid can make an important addition to an investigation case management platform.

Drones are also being used in crime scene analysis. By combining drone technology with 3D mapping technology, police are able to make a navigable rendering of the crime scene based on aerial photographs. This can be used to recreate scenarios such as traffic accidents, or to search for previously unnoticed details in a crime scene.

Search and rescue missions are also aided by drone technology. When lives are on the line, time is of the essence. A drone can cover large areas in a short amount of time, and with a thermal imaging camera attached, it can more easily spot a person than human eyes can – especially in the dark. Drones can also be used to monitor large crowds, not only to observe any possible criminal actions, but also to see if any person in the crowd needs medical assistance but cannot signal for it.

Search and rescue missions are also aided by drone technology. When lives are on the line, time is of the essence. A drone can cover large areas in a short amount of time, and with a thermal imaging camera attached, it can more easily spot a person than human eyes can – especially in the dark. Drones can also be used to monitor large crowds, not only to observe any possible criminal actions, but also to see if any person in the crowd needs medical assistance but cannot signal for it.

Drones are an extremely useful technology and are only becoming better and more affordable. Law enforcement can utilize them not only to better prevent crime, but to reduce the risk that officers take in the field every day. And in a situation where officers are putting their lives on the line, it’s good to have a friend than can fly.

Category Archives: law enforcement

Big Data Surveillance: The Case of Policing

Posted by Douglas Wood, CEO of Case Closed Software – a leader in investigation software and analytics for law enforcement.

Headquartered here in Central Texas, I recently had an opportunity to have coffee with Dr. Sarah Brayne, Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology at The University of Texas at Austin. Ms. Brayne had just published an interesting article in The American Sociological Review. The article is titled Big Data Surveillance: The Case of Policing.

The article examines the intersection of two emerging developments: the increase in surveillance and the massive exploration of “big data.” Drawing on observations and interviews conducted within the Los Angeles Police Department, Sarah offers an empirical account of how the adoption of big data analytics does—and does not—transform police surveillance practices.

She argues that the adoption of big data analytics facilitates may amplify previous surveillance practices, and outlines the following findings:

- Discretionary assessments of risk are supplemented and quantified using risk scores.

- Data tends to be used for predictive, rather than reactive or explanatory, purposes. (Here, Crime Tech Weekly would want to differentiate between predictive analytics and investigation analytics)

- The proliferation of automatic alert systems makes it possible to systematically surveil an unprecedentedly large number of people.

- The threshold for inclusion in law enforcement databases (gang databases, criminal intelligence data, etc) is lower, now including individuals who have not had direct police contact. (Here again, Crime Tech Weekly would point out that adherence to criminal intelligence best practices vastly reduces this likelihood)

- Previously separate data systems are merged, facilitating the spread of surveillance into a wide range of institutions.

Based on these findings, Sarah develops a theoretical model of big data surveillance that can be applied to institutional domains beyond the criminal justice system. Finally, she highlights the social consequences of big data surveillance for law and social inequality.

The full PDF report can be downloaded via Sage Publishing by clicking here. Or, if you have general comments or questions and do not wish to download the full version, please feel free to contact us through the form below. Crime Tech Weekly will be happy to weigh in.

[contact-form][contact-field label=”Name” type=”name” required=”1″ /][contact-field label=”Email” type=”email” required=”1″ /][contact-field label=”Website” type=”url” /][contact-field label=”Comment” type=”textarea” required=”1″ /][/contact-form]

Criminal Intelligence Management: Best Practices

Criminal intelligence analysts provide a key element of effective law enforcement, at both the tactical and strategic levels. Analysts study information related to suspects, trends, known criminals, and more. Through a process of gathering evaluating this information, trained intelligence analysts identify associations across various illegal activities over many locations.

Government decisions and policies are heavily influenced by the insights provided by the criminal intelligence analyst, and police investigations use the intelligence in support of their missions. To that end, the main functions of criminal intelligence analysts include:

Government decisions and policies are heavily influenced by the insights provided by the criminal intelligence analyst, and police investigations use the intelligence in support of their missions. To that end, the main functions of criminal intelligence analysts include:

- Supporting law enforcement activities and large-scale investigations

- Providing an ongoing analysis of potential threats to public safety

- Helping senior officials and policy makers to deal with ever-evolving challenges and uncertainty

There are both tactical and strategic elements to the role of the criminal intelligence analyst. These categories differ with respect to the minutia of details, and the ‘customer’ or end-user of the intelligence.

A. Tactical Criminal Intelligence

Criminal intelligence of a tactical nature attempts to achieve a specific outcome related to law enforcement. Perhaps a disruption of organized criminal groups, a search warrant, seizure of assets, or an arrest.

Tactical criminal intelligence includes:

- The identification of potential connections between people, places, and other entities of interest… and their potential involvement in unlawful activities;

- Recognizing and reporting important gaps in intelligence data;

- Designing and creating detailed dossiers of suspected or confirmed criminals.

B. Strategic Criminal Intelligence

B. Strategic Criminal Intelligence

Strategic analysis of criminal intelligence is expected to continuously educate policy makers and senior officials about current and evolving criminal activities and patterns. The benefits of strategic analysis tend to be realized over a longer period of time than does tactical analysis.

Emerging criminal trends and activities sit at the core of strategic intelligence analysis. The intelligence can provide advanced warning of potential threats, and can provide law enforcement officials with the information required to prepare their agencies for emerging illegal actions.

Strategic criminal intelligence analysis includes the recognition and documentation of:

- Evolving trends and patterns of illegal activities

- Developing threats

- Modus operandi

- The possible effect of demographics, technologies, and evolving socio-economic factors on criminal activities

D. Abuse and Misuse of Criminal Intelligence

D. Abuse and Misuse of Criminal Intelligence

The misuse and/or improper storage and unauthorized access to sensitive criminal intelligence data has always been a concern of civil liberty advocates, and has recently been brought to light again with stories regarding misuse of California’s CalGang database. Given the diverse and growing requirements of criminal intelligence management, certain best-practices and policies have evolved in order to help law enforcement agencies collect, store, and disseminate this important criminal intelligence without invading individual rights to privacy.

E. Best Practices for Criminal Intelligence Management

Specifically, 28 CFR Part 23 is a federal regulation that provides guidance to law enforcement agencies on the standards for implementing and operating federally funded criminal intelligence systems that cross jurisdictions. The protection of individual constitutional rights and civil liberties sits at the core of 28 CFR Part 23. Every American, of course, is afforded a reasonable expectation of privacy. The guidelines outline specific methods to gather, store, disseminate, review, and purge criminal intelligence data.

Specifically, 28 CFR Part 23 is a federal regulation that provides guidance to law enforcement agencies on the standards for implementing and operating federally funded criminal intelligence systems that cross jurisdictions. The protection of individual constitutional rights and civil liberties sits at the core of 28 CFR Part 23. Every American, of course, is afforded a reasonable expectation of privacy. The guidelines outline specific methods to gather, store, disseminate, review, and purge criminal intelligence data.

Recommending the use of these guidelines is The National Criminal Intelligence Sharing Plan (NCISP). NCISP suggests that the regulations ensure that the operations of a criminal intelligence system protect the rights and privacy of individuals and organizations. Importantly, The NCISP suggests that criminal intelligence groups adhere to 28 CFR Part 23, irrespective of whether or not the system was implemented using federal funds and grants.

The criminal intelligence guidelines prescribed by 28 CFR Part 23 have been identified as the minimal policies and rules for sharing data across law enforcement agencies.

The best practices prescribed within the regulation include specific guidelines related to:

- Proper procedures for querying, reviewing, sharing, validating, and purging of criminal intelligence data.

- Multi-jurisdictional memorandums and participation agreements (if applicable).

- The gathering and submission of criminal intelligence information.

- The definition of key criminal intelligence terminology, including ‘the right to know’ and ‘the need to know’.

- The specific activities that may or may not be maintained within the criminal intelligence system.

- Individual rights to access the criminal intelligence systems.

- Security requirements including the auditing and inspection of data.

F. An Excellent Solution

IntelNexus™ from software developer Crime Tech Solutions is an affordable, yet powerful criminal intelligence management system that complies with the regulations and best practices set forth in 28 CFR Part 23. Whether or not an agency (or agencies) absolutely require compliance to 28 CFR Part 23, the software lays out a framework and enforces the principles that should be incorporated into the criminal intelligence database. IntelNexus offers the foundation for gathering, storing, maintaining, sharing, authenticating, and purging criminal intelligence while ensuring the privacy and civil rights afforded to us all.

IntelNexus™ from software developer Crime Tech Solutions is an affordable, yet powerful criminal intelligence management system that complies with the regulations and best practices set forth in 28 CFR Part 23. Whether or not an agency (or agencies) absolutely require compliance to 28 CFR Part 23, the software lays out a framework and enforces the principles that should be incorporated into the criminal intelligence database. IntelNexus offers the foundation for gathering, storing, maintaining, sharing, authenticating, and purging criminal intelligence while ensuring the privacy and civil rights afforded to us all.

The company also develops the popular Case Closed™ investigation case management software, and provides a suite of advanced crime analytics and link analysis software.

Overland Park senior crime analyst Jamie May joins Crime Tech Solutions

September 16, 2016 – (Leander, TX) Crime Tech Solutions, a fast-growing provider of low cost / high performance crime fighting software and analytics is delighted to announce the addition of Jamie May as senior analyst and strategic advisor to the company.

Ms. May has spent over 17 years as a crime and intelligence analyst for Overland Park Police Department in Kansas, and is a recognized expert in crime analysis, mapping, and criminal intelligence. She has sat on critical crime analysis committees including the International Association of Crime Analysts’ Ethics Committee (IACA) and is a past Vice President / Secretary at Mid American Regional Crime Analyst Network (MARCAN).

Ms. May has spent over 17 years as a crime and intelligence analyst for Overland Park Police Department in Kansas, and is a recognized expert in crime analysis, mapping, and criminal intelligence. She has sat on critical crime analysis committees including the International Association of Crime Analysts’ Ethics Committee (IACA) and is a past Vice President / Secretary at Mid American Regional Crime Analyst Network (MARCAN).

“Jamie brings an incredible amount of user experience and innovation to the company”, said Kevin Konczal, Crime Tech Solutions’ VP of Sales. “She’s been active in this community for years, and co-authored the ground-breaking guide, GIS in Law Enforcement: Implementation Issues and Case Studies.”

“To me, Crime Tech Solutions represents a truly innovative company that understands how to develop and market very good technology at prices that most agencies can actually afford”, said Ms. May. “I’m looking forward to being part of the continued growth here.”

In her role with the company, Ms. May will interact with customers and prospects to help align the company’s solution strategy with market and user requirements.

Crime Tech Solutions, who earlier this year acquired TN based Case Closed Software, delivers unique value to customers with comprehensive investigative case management software, sophisticated link analysis tools, criminal intelligence management software, and crime mapping technology that includes some of the industry’s best analytics and reporting capabilities.

Crime Tech Solutions, who earlier this year acquired TN based Case Closed Software, delivers unique value to customers with comprehensive investigative case management software, sophisticated link analysis tools, criminal intelligence management software, and crime mapping technology that includes some of the industry’s best analytics and reporting capabilities.

Using crime analysis solutions to take a ‘Byte’ out of crime

Posted by Crime Tech Solutions

Posted by Crime Tech Solutions

Law enforcement agencies everywhere are tasked with reducing and investigating crime with fewer and fewer resources at their disposal. “To protect and serve” is the highest responsibilities one can sign up for, particularly in light of recent well-publicized criticisms of police by activists in every city.

That responsibility weighs even heavier in a world with no shortage of criminals and terrorists. There’s never enough money in the budget to adequately deal with all of the issues that face an individual agency on a daily basis. Never enough feet on the street, as they say.

New Tools for Age-Old Problems

Perhaps that’s why agencies everywhere are moving to fight crime with an evolving 21st century weapon – law enforcement software including investigative case management, link and social network analysis, and, importantly, crime analytics with geospatial and temporal mapping.

Crime analytics and investigation software have proven themselves to be valuable tools in thwarting criminal activity by helping to better define resource allocation, target investigations more accurately, and enhancing public safety,

According to some reports, law enforcement budgets have been reduced by over 80% since the early 2000s. Still, agencies are asked to do more and more, with less and less.

Analytics in Policing

Analytics in law enforcement play a key role in helping law enforcement agencies better forecast what types of crimes are most likely to occur in a certain area within a certain window of time. While no predictive analytics solution offers the clarity of a crystal ball, they can be effective in affecting crime reduction and public safety.

Predictive analysis, in essence, is taking data from disparate sources, analyzing them and then using the results to anticipate, prevent and respond more effectively to future crime. Those disparate data sources typically include historical crime data from records management systems, calls for service/dispatch information, tip lines, confidential informant information, and specialized criminal intelligence data.

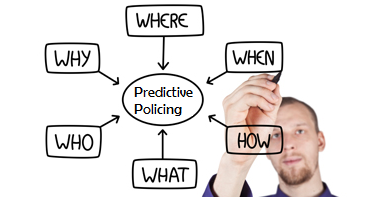

The Five W’s of Predictive Analytics

Within this disparate data lie the 5 W’s of information that can be used by crime analysis software to build predictions. Those key pieces include:

- Arrest records – who committed crimes

- Geospatial data – where crimes have occurred

- Temporal data – when crimes have occurred

- Statistical data – what crimes have occurred

- Investigation data – why (and how) the crimes occurred

Using the 5 W’s, agencies are able to gain insight and make predictions about likely future criminal behavior. For example, if a certain type of crime (what) tends to occur in ‘this’ area (where) at ‘this’ time (when), and by ‘this’ type of individual (who) for ‘this’ reason (why)… it would be wise to deploy resources in that area at that time in order to prevent the incidents from ever occurring. This, of course, is a dramatic over-simplification of the types of analytics that make up predictive policing, but illustrates the general concept well.

Although criminals will always try to be one step ahead of the law, agencies deploying predictive analytics are able to maximize the effectiveness of its staff and other resources, increasing public safety, and keeping bad guys off the street.

More about Crime Tech Solutions

Crime Tech Solutions is an Austin, TX based provider of crime and fraud analytics software for commercial and law enforcement groups. Our offerings include sophisticated Case Closed™ investigative case management and major case management, GangBuster™ gang intelligence software, powerful link analysis software, evidence management, mobile applications for law enforcement, comprehensive crime analytics with mapping and temporal reporting, and 28 CFR Part 23 compliant criminal intelligence database management systems.

NBC News gets rare look at NYPD CompStat meeting

Posted by Tyler Wood, Operations Manager at Crime Tech Solutions.

NBC News was recently allowed a rare opportunity to sit in on a CompStat (computer statistics) meeting with the New York Police Department and they shared their experience with their viewers.

Watch the short video HERE.

(NOTE: Crime Tech Solutions is an Austin, TX based provider of crime and fraud analytics software for commercial and law enforcement groups. We proudly support the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE), International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP), Association of Law Enforcement Intelligence Units (LEIU) and International Association of Crime Analysts (IACA). Our offerings include sophisticated link analysis software, comprehensive crime analytics with mapping and predictive policing, and criminal intelligence database management systems.)

China building big data platform for pre-crime

Re-posted by Crime Tech Solutions – Your Source for Investigation Software

It’s “precrime” meets “thoughtcrime.” China is using its substantial surveillance apparatus as the basis for a “unified information environment” that will allow authorities to profile individual citizens based upon their online behaviors, financial transactions, where they go, and who they see. The authorities are watching for deviations from the norm that might indicate someone is involved in suspicious activity. And they’re doing it with a hand from technology pioneered in the US.

As Defense One’s Patrick Tucker reports, the Chinese government is leveraging “predictive policing” capabilities that have been used by US law enforcement, and it has funded research into machine learning and other artificial intelligence technologies to identify human faces in surveillance video. The Chinese government has also used this technology to create a “Situation-Aware Public Security Evaluation (SAPE) platform” that predicts “security events” based on surveillance data, which includes anything from actual terrorist attacks to large gatherings of people.

As Defense One’s Patrick Tucker reports, the Chinese government is leveraging “predictive policing” capabilities that have been used by US law enforcement, and it has funded research into machine learning and other artificial intelligence technologies to identify human faces in surveillance video. The Chinese government has also used this technology to create a “Situation-Aware Public Security Evaluation (SAPE) platform” that predicts “security events” based on surveillance data, which includes anything from actual terrorist attacks to large gatherings of people.

The Chinese government has plenty of data to feed into such systems. China invested heavily in building its surveillance capabilities in major cities over the past five years, with spending on “domestic security and stability” surpassing China’s defense budget—and turning the country into the biggest market for security technology. And in December, China’s government gained a new tool in surveillance: anti-terrorism laws giving the government even more surveillance powers and requiring any technology companies doing business in China to provide assistance in that surveillance.

The law states that companies “shall provide technical interfaces, decryption and other technical support and assistance to public security and state security agencies when they are following the law to avert and investigate terrorist activities”—in other words, the sort of “golden key” that FBI Director James Comey has lobbied for in the US. For obvious reasons, the Chinese government is particularly interested in the outcome of the current legal confrontation between the FBI and Apple over the iPhone used by Syed Farook.

Bloomberg reports that China is harnessing all that data in an effort to perform behavioral prediction at an individual level—tasking the state-owned defense contractor China Electronics Technology Group to develop software that can sift through the online activities, financial transactions, work data, and other behavioral data of citizens to predict which will perform “terrorist” acts. The system could watch for unexpected transfers of money, calls overseas by individuals with no relatives outside the country, and other trigger events that might indicate they were plotting an illegal action. China’s definition of “terrorism” is more expansive than that of many countries.

At a news conference in December, China Electronics Technology Group Chief Engineer Wu Manqing told reporters, “We don’t call it a big data platform, but a united information environment… It’s very crucial to examine the cause after an act of terror, but what is more important is to predict the upcoming activities.”

__

(NOTE: Crime Tech Solutions is an Austin, TX based provider of crime and fraud analytics software for commercial and law enforcement groups. We proudly support the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE), International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP), Association of Law Enforcement Intelligence Units (LEIU) and International Association of Crime Analysts (IACA). Our offerings include sophisticated link analysis software, comprehensive crime analytics with mapping and predictive policing, and criminal intelligence database management systems.)

Technology and the fight against terrorism

Posted by Crime Tech Solutions

From CNN…

http://money.cnn.com/2015/11/24/technology/targeting-terror-intelligence-isis/index.html?iid=ob_lockedrail_bottomlarge&iid=obnetwork

http://money.cnn.com/2015/11/24/technology/targeting-terror-intelligence-isis/index.html?iid=ob_lockedrail_bottomlarge&iid=obnetwork

(NOTE: Crime Tech Solutions is an Austin, TX based provider of crime and fraud analytics software for commercial and law enforcement groups. We proudly support the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE), International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP), Association of Law Enforcement Intelligence Units (LEIU) and International Association of Crime Analysts (IACA). Our offerings include sophisticated link analysis software, comprehensive crime mapping and predictive policing, and criminal intelligence database management systems.)

What is Crime Analysis?

Posted by Tyler Wood Crime Tech Solutions, your source for investigation software.

The information provided on this page comes primarily from Boba, R. (2008: Pages 3 through 6) Crime Analysis with Crime Mapping. For a full discussion of the crime analysis discipline, refer to the book which can be obtained through www.sagepub.com.

Over the past 20 years, many scholars have developed definitions of crime analysis. Although definitions of crime analysis differ in specifics, they share several common components: all agree that crime analysis supports the mission of the police agency, utilizes systematic methods and information, and provides information to a range of audiences. Thus, the following definition of crime analysis is used as the foundation of this initiative:

Crime analysis is the systematic study of crime and disorder problems as well as other police–related issues—including sociodemographic, spatial, and temporal factors—to assist the police in criminal apprehension, crime and disorder reduction, crime prevention, and evaluation.

Clarification of each aspect of this definition helps to demonstrate the various elements of crime analysis. Generally, to study means to inquire into, investigate, examine closely, and/or scrutinize information. Crime analysis, then, is the focused and systematic examination of crime and disorder problems as well as other police-related issues. Crime analysis is not haphazard or anecdotal; rather, it involves the application of social science data collection procedures, analytical methods, and statistical techniques.

More specifically, crime analysis employs both qualitative and quantitative data and methods. Crime analysts use qualitative data and methods when they examine non-numerical data for the purpose of discovering underlying meanings and patterns of relationships. The qualitative methods specific to crime analysis include field research (such as observing characteristics of locations) and content analysis (such as examining police report narratives). Crime analysts use quantitative data and methods when they conduct statistical analysis of numerical or categorical data. Although much of the work in crime analysis is quantitative, crime analysts use simple statistical methods, such as frequencies, percentages, means, and rates. Typical crime analysis tools include link analysis and crime mapping software.

The central focus of crime analysis is the study of crime (e.g., rape, robbery, and burglary); disorder problems (e.g., noise complaints, burglar alarms, and suspicious activity); and information related to the nature of incidents, offenders, and victims or targets of crime (targets refer to inanimate objects, such as buildings or property). Crime analysts also study other police-related operational issues, such as staffing needs and areas of police service. Even though this discipline is called crime analysis, it actually includes much more than just the examination of crime incidents.

Although many different characteristics of crime and disorder are relevant in crime analysis, the three most important kinds of information that crime analysts use are sociodemographic, spatial, and temporal. Sociodemographic information consists of the personal characteristics of individuals and groups, such as sex, race, income, age, and education. On an individual level, crime analysts use sociodemographic information to search for and identify crime suspects. On a broader level, they use such information to determine the characteristics of groups and how they relate to crime. For example, analysts may use sociodemographic information to answer the question, “Is there a white, male suspect, 30 to 35 years of age, with brown hair and brown eyes, to link to a particular robbery?” or “Can demographic characteristics explain why the people in one group are victimized more often than people in another group in a particular area?”

The spatial nature of crime and other police-related issues is central to understanding the nature of a problem. In recent years, improvements in computer technology and the availability of electronic data have facilitated a larger role for spatial analysis in crime analysis. Visual displays of crime locations (maps) and their relationship to other events and geographic features are essential to understanding the nature of crime and disorder. Recent developments in criminological theory have encouraged crime analysts to focus on geographic patterns of crime, by examining situations in which victims and offenders come together in time and space.

Finally, the temporal nature of crime, disorder, and other police-related issues is a major component of crime analysis. Crime analysts conduct several levels of temporal analysis, including (a) examination of long-term patterns in crime trends over several years, the seasonal nature of crime, and patterns by month; (b) examination of mid-length patterns, such as patterns by day of week and time of day; and (c) examination of short-term patterns, such as patterns by day of the week, time of day, or time between incidents within a particular crime series.

The final part of the crime analysis definition—”to assist the police in criminal apprehension, crime and disorder reduction, crime prevention, and evaluation” generally summarizes the purpose and goals of crime analysis. The primary purpose of crime analysis is to support (i.e., “assist”) the operations of a police department. Without police, crime analysis would not exist as it is defined here.

The first goal of crime analysis is to assist in criminal apprehension, given that this is a fundamental goal of the police. For instance, a detective may be investigating a robbery incident in which the perpetrator used a particular modus operandi (i.e., method of the crime). A crime analyst might assist the detective by searching a database of previous robberies for similar cases.

Another fundamental police goal is to prevent crime through methods other than apprehension. Thus, the second goal of crime analysis is to help identify and analyze crime and disorder problems as well as to develop crime prevention responses for those problems. For example, members of a police department may wish to conduct a residential burglary prevention campaign and would like to target their resources in areas with the largest residential burglary problem. A crime analyst can assist by conducting an analysis of residential burglary to examine how, when, and where the burglaries occurred along with which items were stolen. The analyst can then use this information to develop crime prevention suggestions, (such as closing and locking garage doors) for specific areas.

Many of the problems that police deal with or are asked to solve are not criminal in nature; rather, they are related to quality of life and disorder. Some examples include false burglar alarms, loud noise complaints, traffic control, and neighbor disputes. The third goal of crime analysis stems from the police objective to reduce crime and disorder. Crime analysts can assist police with these efforts by researching and analyzing problems such as suspicious activity, noise complaints, code violations, and trespass warnings. This research can provide officers with information they can use to address these issues before they become more serious criminal problems.

The final goal of crime analysis is to help with the evaluation of police efforts by determining the level of success of programs and initiatives implemented to control and prevent crime and disorder and measuring how effectively police organizations are run. In recent years, local police agencies have become increasingly interested in determining the effectiveness of their crime control and prevention programs and initiatives. For example, an evaluation might be conducted to determine the effectiveness of a two-month burglary surveillance or of a crime prevention program that has sought to implement crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED) principles within several apartment communities. Crime analysts also assist police departments in evaluating internal organizational procedures, such as resource allocation (i.e., how officers are assigned to patrol areas), realignment of geographic boundaries, the forecasting of staffing needs, and the development of performance measures. Police agencies keep such procedures under constant scrutiny in order to ensure that the agencies are running effectively.

In summary, the primary objective of crime analysis is to assist the police in reducing and preventing crime and disorder. Present cutting edge policing strategies, such as hotspots policing, problem-oriented policing, disorder policing, intelligence-led policing, and CompStat management strategies, are centered on directing crime prevention and crime reduction responses based on crime analysis results. Although crime analysis is recognized today as important by both the policing and the academic communities, it is a young discipline and is still being developed. Consequently, it is necessary to provide new and experienced crime analysts with training and assistance that improves their skills and provides them examples of best practices from around the country and the world. http://crimetechsolutions.com

Policing in my hometown (Winnipeg) gets smart

Posted by Douglas Wood, Crime Tech Solutions

As a native Winnipeg boy, this article in the Winnipeg Sun caught my attention…

The government of Manitoba, Canada won’t be making good on its 2011 election pledge to put an extra 50 cops on the streets to combat crime and keep Winnipeg neighborhoods safe.

The government of Manitoba, Canada won’t be making good on its 2011 election pledge to put an extra 50 cops on the streets to combat crime and keep Winnipeg neighborhoods safe.

That may seem odd for a city with the highest violent crime rate in the country. But as policing resources shift away from boots on the ground to more crime-analysis based law enforcement, it’s not more sworn officers the Winnipeg Police Service wants, it’s more resources for so-called smart policing strategies.

“The interest of Winnipeg Police Service is not in officers so much as in crime analysis and smart policing and they have a different approach,” Justice Minister Gord Mackintosh told a legislative committee on Monday. “They do not have an interest in just adding more.” The New Democratic Party promised voters during the last provincial election that it would fund 50 additional officers if re-elected. But four years later, the province has only funded 23 more officers. And there won’t be any new funding for more officers, said Mackintosh.

“The commitment was 50 more officers and we’re now at the equivalent of 23,” said Mackintosh. “The city has requested that the election commitment not be implemented as enunciated during the campaign.” It’s a major shift from years past when provincial parties regularly pledged to put more cops on the street by directly funding the Winnipeg Police Service. The former government was the first to make the promise in 1995 when it promised 40 more police officers for Winnipeg.

The province now directly pays for the salaries and benefits of 172 Winnipeg officers, according to a 2014 report.

And while that funding is expected to continue, the city doesn’t want more money for cops. They want it to help fund other aspects of policing, including more preventative measures, said Mackintosh.

“This is a different approach that is gaining momentum not just here in Winnipeg but in other jurisdictions across the continent,” said Mackintosh. “It’s really about hot spot policing now, it’s about data analysis, looking at the types of offences where they occur, the time of day.” Winnipeg police board chairman Coun. Scott Gillingham confirmed the city isn’t looking for more funding to expand the police complement further. He says police are looking to hire more crime analysts, which can be civilians, not more cops.

“The opportunity and the need would be to focus on preventative measures through things like the smart policing initiative (and) intelligence-led policing,” said Gillingham.

What police also need, though, is more help with the additional workload they’ve taken on as they deal increasingly with mental health patients, Child and Family Services cases and soaring domestic abuse calls.

Police may be moving towards a more data-based approach to law enforcement, but they’ve also become a service of last resort for a growing number of tough social service cases, including tracking down chronic runaway wards of the state on a regular basis.

Which means they’re going to need a lot more support from provincial agencies to pick up some of that slack.

Winnipeg police may not need more boots on the ground. After all, Winnipeg does have the most cops per capita of any Canadian city, and has for some time.

But the province is going to have to figure out how to better manage the social service cases that are landing increasingly at the doorstep of police.