The following article originally appeared at In Public Safety, and is a highly recommended read. It was written by Erik Kleinsmith at American Military University.

Crime Tech Weekly is posting the article in its entirety for our readers’ convenience…

By Erik Kleinsmith

Staff, Intelligence Studies, American Military University

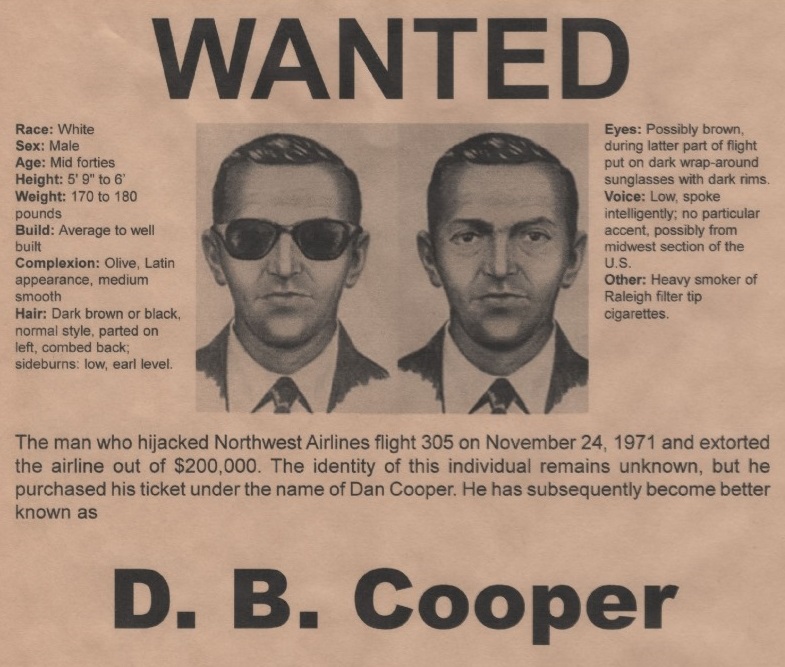

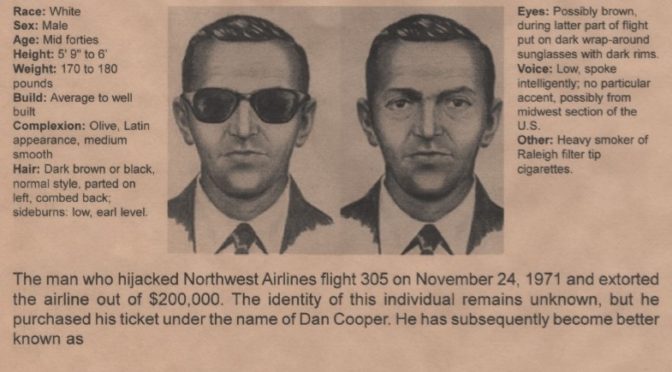

On November 24, 1971, a man using the name Dan Cooper purchased a $35 one-way airline ticket from Portland, Oregon, to Seattle, Washington. Not long after takeoff, he hijacked Northwest Orient Flight 305 and demanded $200,000 in cash along with two parachutes, which he received upon landing in Seattle. He then ordered the plane to take off and fly to Mexico City; during that flight, he jumped from the aircraft into the Oregon wilderness, securing his place as the only unsolved case in FAA history.

In early 2011, following a host of other investigations — both private and government-led — Tom Colbert picked up the trail of the man now known as D.B. Cooper. As an investigative reporter and producer living in Southern California, Colbert was tipped off by a source in the illicit drug trade who had credible — albeit circumstantial — evidence that D.B. Cooper was alive and living in California. Over the next few years, Colbert invested incredible amounts of time and personal resources toward tackling a 45-year-old mystery that so many other investigators before him had failed to solve.

A New Approach to Finding D.B. Cooper

Colbert assembled a large group of leading private investigators, detectives, attorneys, profilers and other subject matter experts into a group he called the “Cold Case Team.” He also knew he needed the expertise of intelligence professionals to help him organize and analyze all the evidence related to this case. While intelligence analysts almost always focus on using their skills for predictive analysis predictive analysis (i.e., what’s going to happen), Colbert knew having people proficient in intelligence collection and analysis would provide unique insight into a case that was decades old.

In December 2011, Colbert elicited my help while I was involved in an Army intelligence training contract. We had been associates and friends for a few years and he knew about my involvement in the Able Danger program. As a student, practitioner, developer and instructor of intelligence methodology, I was interested in his investigation because it was another chance for me to adapt intelligence analytical methods to a cold (very cold) case. I immediately agreed to support his efforts; he sent me a copy of a dossier on the man he suspected was D.B. Cooper.

It contained photos, maps, interview summaries and many other pieces of evidence connecting this man to the D.B. Cooper incident. Much of the initial information was secondhand and circumstantial, so Colbert was using it to provide further investigative leads for the Cold Case Team members.

Here is where I make my quick disclaimer: Collecting information on U.S. persons for intelligence purposes is prohibited by several federal regulations with very few specific exceptions. Even though I would be supporting a private investigation, I was working as a defense contractor at the time and therefore felt it was important to follow the spirit of these restrictions by creating products based only upon what the Cold Case Team provided. Neither myself nor my colleague independently searched for or collected any additional information for any part of this investigation.

That being said, it was an exceptional opportunity to use analytical intelligence techniques to assist in this investigation.

Using Link Analysis Techniques in the Investigation

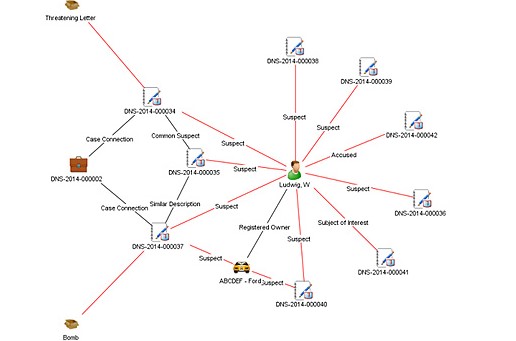

In his meetings with various law enforcement officials, Colbert had grown frustrated that no one was taking the time to look through the dossier and consider the evidence. I gave it to one of my senior instructors, David D’Alessio, and asked him to make a link chart of associations using one of the best link analysis software programs available to us. A link chart is a graphic representation of the people, events, and significant items of interest (such as a bank account or address) associated with a particular subject. The key to these charts are the associations or “links” between each of the people, events and items in it.

Creating this chart was a painstaking process because D’Alessio had to go through each paragraph line by line, identify the relative linkages between entities and enter them into the software program. The initial link chart started with the main suspect and then drew graphic linkages to all his known associates their connections to third parties, and a host of other associations to events, locations, aliases and specific pieces of physical evidence. Working with D’Alessio and Colbert over several iterations of this chart, we ended up with a 3×2 foot poster that, to the untrained eye, looked a lot like charts shown in court or on television shows like Law and Order. There were hundreds of links to the main suspect, the many aliases he used over the years to include military records and associations that placed him in the vicinity of the Portland, Oregon area during the time of the hijacking.

The benefit of link analysis charts is that they do more than just show connections between entities. A link chart tells a comprehensive visual story and conveys a dynamic and detailed summary of information from the document supporting it. This technique proved immensely successful, as the visual representation helped capture attention and interest from outside parties.

How Intelligence Analysis Aided in the Investigation

Besides taking text-based information and turning it into a graphic visualization for presentation purposes, a link chart also helped the investigation in other ways. First, Colbert and his team were able to see gaps in the information where investigators needed to dig deeper. He could also see which links were strong and which were weak or tenuous. The team could then plan their investigations more effectively by identifying which gaps needed to be filled and prioritize how to best use their limited resources.

This chart also had a psychological value to the Cold Case Team. In 2013, one of the team’s private investigators presented it directly to the suspect and asked him to come forward. The hope was that once the suspect knew there was a vast amount of information on the identity of D.B. Cooper (not to mention it featured his picture right at the center). Revealing this chart helped Colbert enter into negotiations with the suspect’s lawyer and he came very close to a deal that would potentially involve an admission. Unfortunately, Colbert and the Cold Case Team were turned down at the last minute due to what we believe was his fear of being connected to other illicit activities.

Why Law Enforcement Must Partner More Often with Intelligence Agencies

Ultimately, this case demonstrates that intelligence analysis can play a crucial part in law enforcement investigations, both as a predictive asset as well as an investigative one. The D.B. Cooper investigation is decades old, but there are many other cases that are not. Other law enforcement agencies can use the techniques tested in this case to assist with other unsolved crimes, missing persons and patterns of criminal activity. It’s important for law enforcement authorities to remember that analysts in the intelligence field bring with them a toolkit that provides both unique and specialized analytical methods that can offer new perspectives. Bringing intelligence analysts into the fold of law enforcement can enhance a crime-solving team.

Ultimately, this case demonstrates that intelligence analysis can play a crucial part in law enforcement investigations, both as a predictive asset as well as an investigative one. The D.B. Cooper investigation is decades old, but there are many other cases that are not. Other law enforcement agencies can use the techniques tested in this case to assist with other unsolved crimes, missing persons and patterns of criminal activity. It’s important for law enforcement authorities to remember that analysts in the intelligence field bring with them a toolkit that provides both unique and specialized analytical methods that can offer new perspectives. Bringing intelligence analysts into the fold of law enforcement can enhance a crime-solving team.

The federal government has awesome capabilities in intelligence collection and investigation but they are not alone. There is an equally awesome, yet untapped capability, in the commercial sector and among academia to support investigations like this and other more current cases. There are uncounted numbers of undergraduate and graduate students in criminal justice, data analysis and intelligence studies courses who would be eager to support a future case. In addition, there are also many retired law enforcement and intelligence professionals who would be eager to lend their experience and subject matter expertise to similar cases and problem sets, if only to satisfy the investigative bug still within them.

While the FBI officially closed its investigation in the D.B. Cooper case earlier this year, it has not been closed in the eyes of the Cold Case Team. This team continues to move forward with its own investigation, relying on intelligence analysis methods to support them and continue to evaluate every bit of evidence in new ways.

Since its introduction nearly a decade ago, big data in the form of analytics has helped police agencies all over the world enhance decision making, improve strategies to combat crime, and ultimately solve—and prevent—more crimes. But while the benefits of mining and critically analyzing huge amounts of data are being realized in other developed countries from the United Kingdom to Canada to New Zealand, U.S. law enforcement agencies have generally been slower to jump on the bandwagon.

Since its introduction nearly a decade ago, big data in the form of analytics has helped police agencies all over the world enhance decision making, improve strategies to combat crime, and ultimately solve—and prevent—more crimes. But while the benefits of mining and critically analyzing huge amounts of data are being realized in other developed countries from the United Kingdom to Canada to New Zealand, U.S. law enforcement agencies have generally been slower to jump on the bandwagon. None of this is news, nor is it a criticism of U.S. police departments. It simply reflects Americans’ independent nature and the way in which law enforcement in this country is structured. It’s the thing that makes us great but, in the case of analytics, it’s also a major factor slowing analytics adoption.

None of this is news, nor is it a criticism of U.S. police departments. It simply reflects Americans’ independent nature and the way in which law enforcement in this country is structured. It’s the thing that makes us great but, in the case of analytics, it’s also a major factor slowing analytics adoption. All of these factors have contributed to slowing the adoption of analytics by U.S. police agencies. They are also complicated by perhaps the most intangible impediment: fear of technology. Whether they like to admit it or not, some law enforcement leaders are more comfortable taking an “old school” approach to police work. They prefer business as usual, which means feet on the street and files stacked on their detectives’ desks, not sleek, state-of-the-art technology.

All of these factors have contributed to slowing the adoption of analytics by U.S. police agencies. They are also complicated by perhaps the most intangible impediment: fear of technology. Whether they like to admit it or not, some law enforcement leaders are more comfortable taking an “old school” approach to police work. They prefer business as usual, which means feet on the street and files stacked on their detectives’ desks, not sleek, state-of-the-art technology. The public is also demanding increased police effectiveness and efficiency. Responding to that pressure, police chiefs are recognizing that big data solutions can have a huge impact on reducing the number of man-hours it takes to sift through mountains of data in order to solve crimes. This is particularly important as law enforcement finds itself confronting not only the standard array of home break-ins, car thefts, and the like, but also the threat of “lone wolf” terrorist attacks, cybercrime, and highly sophisticated international trafficking rings.

The public is also demanding increased police effectiveness and efficiency. Responding to that pressure, police chiefs are recognizing that big data solutions can have a huge impact on reducing the number of man-hours it takes to sift through mountains of data in order to solve crimes. This is particularly important as law enforcement finds itself confronting not only the standard array of home break-ins, car thefts, and the like, but also the threat of “lone wolf” terrorist attacks, cybercrime, and highly sophisticated international trafficking rings. The growing use of cloud computing plays a role in this equation. Storing data in the cloud is becoming accepted as safe and secure, bringing with it economic advantages and removing the need for departments to provide highly specialized IT staff and infrastructure previously required to support analytical solutions.

The growing use of cloud computing plays a role in this equation. Storing data in the cloud is becoming accepted as safe and secure, bringing with it economic advantages and removing the need for departments to provide highly specialized IT staff and infrastructure previously required to support analytical solutions.

Mr. Konczal is a seasoned start-up and marketing expert with over 30 years of diversified business management, marketing and start-up experience in information technology and consumer goods. Additionally, Konczal has over two decades of Public Safety service as a police officer, Deputy Sheriff and Special Agent.

Mr. Konczal is a seasoned start-up and marketing expert with over 30 years of diversified business management, marketing and start-up experience in information technology and consumer goods. Additionally, Konczal has over two decades of Public Safety service as a police officer, Deputy Sheriff and Special Agent. A recent report questions how some police departments are using data to forecast future crimes.

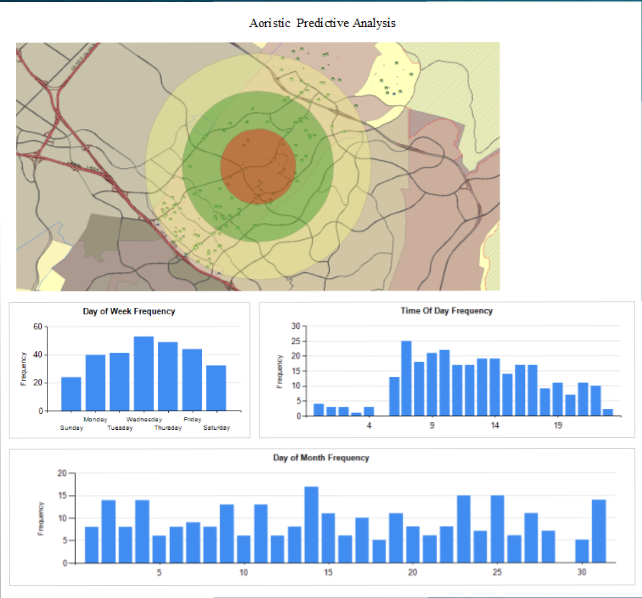

A recent report questions how some police departments are using data to forecast future crimes. ryant worked with the Shawnee, Kansas, Police Department on research that looked at what he calls “smart policing.” In his research and in other work he has read, Bryant said it’s important for police to have a high visibility in crime hot spots, for officers to make connections with the public and for them to avoid staying in crime hot spots for extended periods of time.

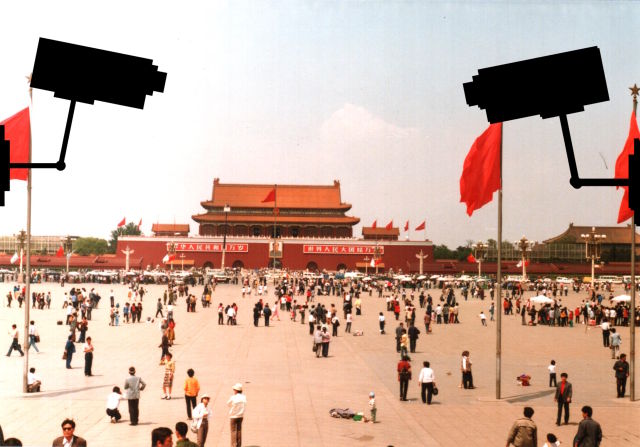

ryant worked with the Shawnee, Kansas, Police Department on research that looked at what he calls “smart policing.” In his research and in other work he has read, Bryant said it’s important for police to have a high visibility in crime hot spots, for officers to make connections with the public and for them to avoid staying in crime hot spots for extended periods of time. Here is another great reason why it is important for agencies to follow best practices in intelligence data management. The regulations behind DOJ 28 CFR Part 23 are meant to help agencies walk the line between effective intelligence gathering and the right to an individual’s privacy.

Here is another great reason why it is important for agencies to follow best practices in intelligence data management. The regulations behind DOJ 28 CFR Part 23 are meant to help agencies walk the line between effective intelligence gathering and the right to an individual’s privacy. As

As