In Part One of this series, I overviewed a generally-accepted definition of Major Cases, and discussed some of the attributes that define them.

In Part Two, I began to probe the ‘types’ of Major Cases – specifically, Single-Incident Major Cases. These are cases that may, under different circumstances, not be Major Cases but for the identity of the victim, the identity of the suspect, the location of the incident, and/or the uniqueness of the crime.

Here in Part Three, I want to discuss the second ‘type’ of Major Cases – Multi-Incident Major Cases and – specifically – the problems associated with trying to investigate a case while related crimes are still occurring. (Spoiler Alert: It’s stressful)

Based upon interviews I have conducted with CID Commanders, Sheriffs, District Attorneys, and other law enforcement experts, there are several types of Multi-Incident Major Cases. Based on the patterns of the crimes, Multi-Incident Major Cases are classified into three basic categories – Mass crimes, Spree crimes, and Serial crimes

Mass Crimes – A Major Case mass crime involves multiple victims at one location during one continuous period of time, whether it is done within a few minutes or over a period of days. The term ‘mass murder’ springs to mind, and invokes images of Dylann Roof(Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in South Carolina), James Holmes (2012 Aurora, CO. shooting in which he killed 12 people and injured 70 others at a movie theater), and James Loughner (2011 Tuscon, AZ shooting that killed 6 people and severely wounded US Representative Gabrielle Giffords).

There are other types of Major Case mass crimes, however, including mass assault, mass human smuggling, and other horrible crimes that need no further illustration here.

Spree Crimes – Spree criminals commit two or more serious crimes with two or more victims, but at more than one location. An important distinction about spree crimes is that there is no ‘cooling off’ period between the crimes.

An unfortunate example of a spree crime is that of Mark Barton. On July 29th, 1999, he walked into his office at Momentum Securities and opened fire, killing four people. Then he went next door to another company and killed five more people. Earlier in the day he had also murdered his wife and their two children. Multiple crimes in multiple locations with no cooling off.

Another example of a spree crime is the armed robber who hits a slew of pre-chosen banks on the same day, terrorizing employees in the process. The examples here are too numerous to mention, but they become Major Cases by virtue of their spree qualities. Again, this shows multiple crimes in multiple locations with no cooling off.

Serial Crimes – Serial criminals commit multiple crimes with multiple victims. Unlike spree criminals, however, serial criminals commit their crimes on distinctly separate occasions. There is a cooling off period between crimes.

Uniquely, serial criminals tend to plan their crimes meticulously and pre-select their victims and locations. Unlike mass crimes and spree crimes, serial crimes are differentiated in that the perpetrator tends to carefully select their victims, have cooling-off periods between crimes, and plan them carefully. Examples of serial criminals (especially serial killers) are far too easy to find and include The Zodiac Killer (in California in the late 1960s), Ted Bundy (confessed to killing 30 women), and Dennis Raider (The BTK Murderer who killed 10 people in Wichita between 1974 and 1991

A unique problem with Multiple Incident Major Cases

The major problem for law enforcement investigating Multiple Incident Major Cases, especially those that fall in the ‘serial’ category, is that new crimes are committed even as the investigation is underway. Resources can be stretched to their thinnest when a new crime is added to the serial list, and the public pressure for an arrest can overwhelm even the hardest of investigators. Hello, stress.

A common attribute of the successful serial crime investigators that I have spoken with is their ability to separate the pressure from the work. The crimes and their timing are unpredictable, the public demand for a resolution is powerfully serious, and ‘interested parties’ (think politicians) are breathing down the investigators’ necks. That’s a lot of pressure.

Just as in any profession, untreated stress can lead to major consequences. These consequences not only affect the individual investigator, but also those with whom he or she has daily contact, including family and friends. The investigators I have spoken with help alleviate the pressure through:

- Taking care of themselves physically,

- Ensuring that workload is spread as evenly as possible, and

- Taking time to partake in leisure and family.

(A quick point of clarity and a disclaimer: Any discussion around the differences between mass criminals, spree criminals, and serial criminals is going to be lively, and is an ongoing source for debate among criminologists. This posting will undoubtedly include characteristics and definitions that some readers may not entirely agree with.)

Douglas Wood is CEO of Crime Technology Solutions | Case Closed Software, a leading provider of serious investigation software to law enforcement, state bureaus, DA offices, and other investigative units. Doug can be reached directly HERE.

Douglas Wood is CEO of Crime Technology Solutions | Case Closed Software, a leading provider of serious investigation software to law enforcement, state bureaus, DA offices, and other investigative units. Doug can be reached directly HERE.

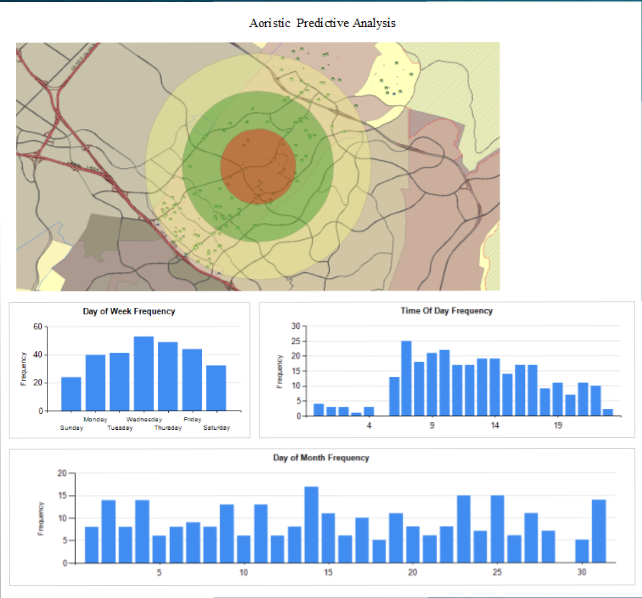

A recent report questions how some police departments are using data to forecast future crimes.

A recent report questions how some police departments are using data to forecast future crimes. How police departments nationwide utilize crime statistics and the software available to patrol officers monitoring incidents has evolved a lot in the past couple decades, Sgt. Tracy Barton with the St. Joseph Police Department said. Barton started as a patrol officer 20 years ago. He said having software like police have today would have been useful.

How police departments nationwide utilize crime statistics and the software available to patrol officers monitoring incidents has evolved a lot in the past couple decades, Sgt. Tracy Barton with the St. Joseph Police Department said. Barton started as a patrol officer 20 years ago. He said having software like police have today would have been useful.

ryant worked with the Shawnee, Kansas, Police Department on research that looked at what he calls “smart policing.” In his research and in other work he has read, Bryant said it’s important for police to have a high visibility in crime hot spots, for officers to make connections with the public and for them to avoid staying in crime hot spots for extended periods of time.

ryant worked with the Shawnee, Kansas, Police Department on research that looked at what he calls “smart policing.” In his research and in other work he has read, Bryant said it’s important for police to have a high visibility in crime hot spots, for officers to make connections with the public and for them to avoid staying in crime hot spots for extended periods of time.