The backbone of any functioning criminal intelligence unit is the strength of its intel files and/or gang records. Best practices for gang intelligence suggests that agencies should regularly update and contribute gang intelligence to a specialized gang intelligence system (aka gang database). These intelligence systems can manage and store thousands or millions of records of gangs, their activities, and their members.

With gang intelligence software, authorized users may read and update specific files, search and retrieve photos/videos/audio, and generally utilize the solution to assist investigation efforts. An example of some attributes stored within a gang intelligence system are:

- Activities

- Locations

- Names

- Vehicles

- Addresses

- Tattoos

- Marks and Scars

- Incidents

- Reports

- Tips

- Aliases

Properly utilized, the gang intelligence system should allow the collection, analysis, storage and retrieval of data that qualifies as criminal intelligence. The data should only be disseminated to agency members with a specific need, and that need should be logged as part of the dissemination.

Gang Intelligence Integrity

With a gang intelligence database, agencies must preserve the integrity of the system through security and access restriction from unauthorized users – internal and external – because of constitutional protection for individuals whose personal information is contained within the system.

Importantly, for gang intelligence, a rigid purging process must be adhered to as this ensures the integrity and credibility of the data. If, for example, a record has not been reviewed or appended for a period of five years, best practices suggest that the record be purged.

Access governance is also critical to gang intelligence systems to ensure integrity of the data entered and maintained and, importantly, to comply with applicable regional, state, and federal laws.

Gang / Criminal Intelligence and U.S. Law

The United States Constitution prohibits the criminalization of mere membership in a gang (or other similar organization). There is nothing illegal about being a gang member, according to our country’s laws. However, it is perfectly legal for agencies to add gang members to the database even if no crime has been committed by that member.

The United States Constitution prohibits the criminalization of mere membership in a gang (or other similar organization). There is nothing illegal about being a gang member, according to our country’s laws. However, it is perfectly legal for agencies to add gang members to the database even if no crime has been committed by that member.

The tracking and storage of this data is widely criticized, however. Opponents suggest that agencies are profiling or targeting groups that are not engaged in criminal activities, and/or installing a ‘guilt by association’ mentality by tracking those members.

Conversely, advocates of gang intelligence database systems know that law enforcement has a legitimate interest in monitoring the individuals and groups engaged in ‘group criminal behavior’.

The back-and-forth between sides creates tension between the rights of society to be protected by law enforcement, and the individual privacy expectations of gang members.

CFR 28 Part 23

The result of these competing interests is something called Code of Federal Regulations, Title 28, Part 23 (CFR 28 Part 23) which details the requirements for gathering, entering, storing, and disseminating information about individuals and organizations (gangs) into an intelligence system.

28 CFR Part 23 was designed as a regulation specific to multi-jurisdictional intelligence systems that have received federal grant funds for the development or purchase of the gang database. It is, however, an excellent guide for individual agencies, as the regulation attempts to fairly balance the intelligence needs of law enforcement against individual privacy requirements. In other words, it helps agencies get their jobs done without violating individual rights.

28 CFR Part 23 was designed as a regulation specific to multi-jurisdictional intelligence systems that have received federal grant funds for the development or purchase of the gang database. It is, however, an excellent guide for individual agencies, as the regulation attempts to fairly balance the intelligence needs of law enforcement against individual privacy requirements. In other words, it helps agencies get their jobs done without violating individual rights.

Compliance with 28 CFR Part 23 in Gang Intelligence

Gang and criminal intelligence data is defined within 28 CFR Part 23 as “data which has been evaluated to determine that:

A) it is relevant to the identification of, and the criminal activity engaged in by, an individual who – or an organization which – is reasonably suspected of involvement in criminal activity, and

B) meets criminal intelligence system submission criteria”

The ‘submission criteria’ is essentially the basis for something to be entered into the gang intelligence system. The criteria include the following:

- A reasonable suspicion that an individual is relevant to the criminal activity

- Prospective information to be entered is relevant to the criminal activity

- Information does not include data related to political, religious, or social views unless that information related directly to the criminal activity that formed the basis for focus on the gang or group

- Information was not obtained in violation of any federal, state, or local law or ordinance

- Information establishes sufficient facts to give trained law enforcement officials a basis to believe that an individual or gang/organization is involved in a definable criminal activity

As referenced above, 28 CFR Part 23 also indicates that information contained within a compliant database or criminal intelligence system must be reviewed and evaluated for relevance and importance every five years. Data that is deemed to be irrelevant and unimportant should be purged from the system. This is true even if the data is discovered to be noncompliant before five years.

Perhaps the most important element of a gang database system complying with 28 CFR Part 23 is that no information whatsoever from the database should be disseminated without a legitimate law enforcement reason, such as criminal investigation cases and charges being filed against a suspect.

Conclusion

If managing a gang intelligence system seems intimidating, it ought not be. If an agency desires to comply with 28 CFR Part 23, the rules for managing such as system are clearly spelled out. If an agency simply wants to collect and manage data outside of the federal guidelines – and has not accepted federal grant monies for such a program – they are free to do so as long as the system meets the security and ‘common sense’ guidelines that protect an individual’s right to privacy.

About the Author

Tyler Wood is Operations Director of Austin, TX based Crime Tech Solutions (www.crimetechsolutions.com). The company develops and deploys low price / high performance software for law enforcement including Case Closed™ investigative case management software, sophisticated Sentinel Visualizer™ link analysis and data visualization software, and CrimeMap Pro™ advanced crime analytics. The company also develops the popular GangBuster™ gang database, and IntelNexus™ criminal intelligence software for 28 CFR Part 23 compliance.

The International Association of Crime Analysts (IACA) 2016 conference is in full swing in Louisville, KY. Here is some good, local video coverage of the event…

The International Association of Crime Analysts (IACA) 2016 conference is in full swing in Louisville, KY. Here is some good, local video coverage of the event… Since its introduction nearly a decade ago, big data in the form of analytics has helped police agencies all over the world enhance decision making, improve strategies to combat crime, and ultimately solve—and prevent—more crimes. But while the benefits of mining and critically analyzing huge amounts of data are being realized in other developed countries from the United Kingdom to Canada to New Zealand, U.S. law enforcement agencies have generally been slower to jump on the bandwagon.

Since its introduction nearly a decade ago, big data in the form of analytics has helped police agencies all over the world enhance decision making, improve strategies to combat crime, and ultimately solve—and prevent—more crimes. But while the benefits of mining and critically analyzing huge amounts of data are being realized in other developed countries from the United Kingdom to Canada to New Zealand, U.S. law enforcement agencies have generally been slower to jump on the bandwagon. None of this is news, nor is it a criticism of U.S. police departments. It simply reflects Americans’ independent nature and the way in which law enforcement in this country is structured. It’s the thing that makes us great but, in the case of analytics, it’s also a major factor slowing analytics adoption.

None of this is news, nor is it a criticism of U.S. police departments. It simply reflects Americans’ independent nature and the way in which law enforcement in this country is structured. It’s the thing that makes us great but, in the case of analytics, it’s also a major factor slowing analytics adoption. All of these factors have contributed to slowing the adoption of analytics by U.S. police agencies. They are also complicated by perhaps the most intangible impediment: fear of technology. Whether they like to admit it or not, some law enforcement leaders are more comfortable taking an “old school” approach to police work. They prefer business as usual, which means feet on the street and files stacked on their detectives’ desks, not sleek, state-of-the-art technology.

All of these factors have contributed to slowing the adoption of analytics by U.S. police agencies. They are also complicated by perhaps the most intangible impediment: fear of technology. Whether they like to admit it or not, some law enforcement leaders are more comfortable taking an “old school” approach to police work. They prefer business as usual, which means feet on the street and files stacked on their detectives’ desks, not sleek, state-of-the-art technology. The public is also demanding increased police effectiveness and efficiency. Responding to that pressure, police chiefs are recognizing that big data solutions can have a huge impact on reducing the number of man-hours it takes to sift through mountains of data in order to solve crimes. This is particularly important as law enforcement finds itself confronting not only the standard array of home break-ins, car thefts, and the like, but also the threat of “lone wolf” terrorist attacks, cybercrime, and highly sophisticated international trafficking rings.

The public is also demanding increased police effectiveness and efficiency. Responding to that pressure, police chiefs are recognizing that big data solutions can have a huge impact on reducing the number of man-hours it takes to sift through mountains of data in order to solve crimes. This is particularly important as law enforcement finds itself confronting not only the standard array of home break-ins, car thefts, and the like, but also the threat of “lone wolf” terrorist attacks, cybercrime, and highly sophisticated international trafficking rings. The growing use of cloud computing plays a role in this equation. Storing data in the cloud is becoming accepted as safe and secure, bringing with it economic advantages and removing the need for departments to provide highly specialized IT staff and infrastructure previously required to support analytical solutions.

The growing use of cloud computing plays a role in this equation. Storing data in the cloud is becoming accepted as safe and secure, bringing with it economic advantages and removing the need for departments to provide highly specialized IT staff and infrastructure previously required to support analytical solutions.

Posted by

Posted by

Mr. Konczal is a seasoned start-up and marketing expert with over 30 years of diversified business management, marketing and start-up experience in information technology and consumer goods. Additionally, Konczal has over two decades of Public Safety service as a police officer, Deputy Sheriff and Special Agent.

Mr. Konczal is a seasoned start-up and marketing expert with over 30 years of diversified business management, marketing and start-up experience in information technology and consumer goods. Additionally, Konczal has over two decades of Public Safety service as a police officer, Deputy Sheriff and Special Agent. A recent report questions how some police departments are using data to forecast future crimes.

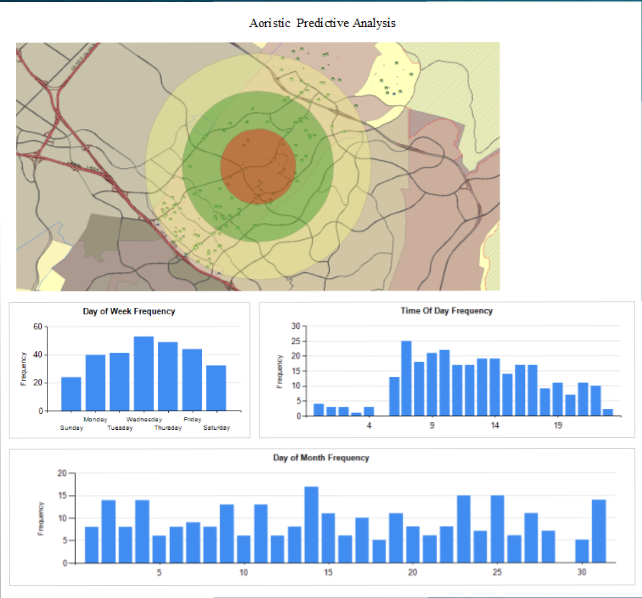

A recent report questions how some police departments are using data to forecast future crimes. ryant worked with the Shawnee, Kansas, Police Department on research that looked at what he calls “smart policing.” In his research and in other work he has read, Bryant said it’s important for police to have a high visibility in crime hot spots, for officers to make connections with the public and for them to avoid staying in crime hot spots for extended periods of time.

ryant worked with the Shawnee, Kansas, Police Department on research that looked at what he calls “smart policing.” In his research and in other work he has read, Bryant said it’s important for police to have a high visibility in crime hot spots, for officers to make connections with the public and for them to avoid staying in crime hot spots for extended periods of time.