Several times each week, I receive an inquiry from a PD, task force, or Sheriff’s office asking if my investigation case management software, Case Closed Software, can interface with a particular Records Management System (RMS). The question stems from the investigation unit’s desire to have a purpose-built, flexible solution designed to help their agents stay organized and work more efficiently.

Let’s face it… RMS software, by and large, is not designed for managing major cases. Agencies know it, and the RMS vendors know it. For them, the notion of managing the complexities of major case investigations is an afterthought at best.

(The answer I give to these inquiries, by the way, is that any good investigation management software should have capabilities to ingest data from other law enforcement products, including RMS).

The more important point, however, is recognizing that criminal investigators gather vasts amounts of information during the course of an investigation. Witness statements, interviews, interrogations, tips, leads, informant statements, audio files, video files, photos, and much more. Too often, agents must rely on their RMS systems which, per above, are not purpose-built for investigations. Investigators also rely heavily on paper files and file cabinets full of notes, search warrants, and physical evidence.

Fortunately, there is an alternative… purpose built investigation case management software that utilizes what I call ‘Case Actions’ as the underlying workflow. Case Actions are the individual actions that an investigation unit takes in pursuit of closing a case. Case Actions are expansive in nature, and include:

- Crime Scene Visits

- Interviews

- Interrogations

- Knock ‘n Talks

- Surveillance

- DNA

- Search Warrants

- Affidavits

- Controlled Buys

- Arrests

… and much, much more. You get the idea, though.

By effectively logging each Case Action in a particular Case, the investigators (and management) are able to quickly and visually recognize the status of the case, and what further actions should be taken. Each Case Action leads to new information… which leads to new Case Actions. And the beat goes on. Hopefully, sooner rather than later, enough information is garnered to close the case. That’s the power of Case Action based workflow.

WIth the Case Action based approach, each Case Action is tied to Persons, Locations, Vehicles, etc. As a result, robust dossiers of these things are built without the individual agent(s) even realizing it.

By utilizing an investigation case management solution that is based upon Case Actions, law enforcement can leverage information from previously-entered data such as telephone numbers, evidence items, addresses, persons, gang members, etc. The Case Actions feed themselves – and each other – to build a valuable repository of investigative information.

An example: A detective has received a tip that Doug Wood is involved in a particular criminal activity. By accessing her Case Action-based system, she quickly learns that Doug Wood has been a Suspect in Case 1 (belonging to an entirely different investigator), and a Witness in Case 2 (belonging to a third investigator).

She also learns (via Case Actions performed by the Gang Unit) that Doug Wood shares an address with a confirmed Gang Member and goes by the nickname ‘Woody’. She also sees Doug’s previous addresses, telephone numbers, work history, social media accounts and so on… each of which has been logged as part of completely unique Case Actions.

That is the power of Case Actions based investigation management software. Because each previous Case Action involving Doug Wood was logged, the current investigator has a goldmine of information at her fingertips.

Case Closed Software is the leading provider of Case Action based investigation case management software for law enforcement. Contact Us for a demo today!

Douglas Wood is CEO of

Douglas Wood is CEO of

Douglas Wood is CEO of

Douglas Wood is CEO of  Tupac was an American rapper and actor who came to embody the 1990s gangsta-rap aesthetic, and was a key figure in the feud between West Coast and East Coast hip hop artists. Simply put… he was famous as hell. Hence, a far-too-routine shooting became a Major Case in the blink of an eye. The case remains unsolved.

Tupac was an American rapper and actor who came to embody the 1990s gangsta-rap aesthetic, and was a key figure in the feud between West Coast and East Coast hip hop artists. Simply put… he was famous as hell. Hence, a far-too-routine shooting became a Major Case in the blink of an eye. The case remains unsolved. After weeks of testimony, and a clear nation-wide division between those who believed Simpson to be innocent and those who believed him guilty, Simpson was acquitted of the murders on October 3, 1995.

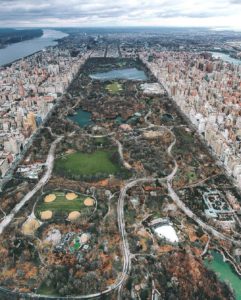

After weeks of testimony, and a clear nation-wide division between those who believed Simpson to be innocent and those who believed him guilty, Simpson was acquitted of the murders on October 3, 1995.  The ‘Met’, as the museum is known, is one of the most-visited and famous museums on the entire planet. Murders don’t happen in world-famous places like this, and the case became the top story on the evening news for months and months. That is one major single-incident Major Case.

The ‘Met’, as the museum is known, is one of the most-visited and famous museums on the entire planet. Murders don’t happen in world-famous places like this, and the case became the top story on the evening news for months and months. That is one major single-incident Major Case. On the morning of December 26, 1996, John Ramsey found his daughter’s body with duct tape over her mouth and a cord twisted around her neck in the basement of the family home. John’s wife, Patsy, says she found a ransom note demanding $118,000 for JonBenét’s return – an amount that is purported to match exactly a recent work-related bonus that John Ramsey had received. Despite these odd circumstances, the couple retained lawyers and were not formally interviewed by police for over 4 months. (The case has never been solved, and Boulder Police have cleared the couple of any wrongdoing.)

On the morning of December 26, 1996, John Ramsey found his daughter’s body with duct tape over her mouth and a cord twisted around her neck in the basement of the family home. John’s wife, Patsy, says she found a ransom note demanding $118,000 for JonBenét’s return – an amount that is purported to match exactly a recent work-related bonus that John Ramsey had received. Despite these odd circumstances, the couple retained lawyers and were not formally interviewed by police for over 4 months. (The case has never been solved, and Boulder Police have cleared the couple of any wrongdoing.)

(July 31, 2018) Crime Technology Solutions, LLC is very pleased to announce that one of the largest District Attorneys offices in the United States has selected them to provide sophisticated crime analytics and criminal intelligence management software. The deal, over a year in the making, will see

(July 31, 2018) Crime Technology Solutions, LLC is very pleased to announce that one of the largest District Attorneys offices in the United States has selected them to provide sophisticated crime analytics and criminal intelligence management software. The deal, over a year in the making, will see  At the core of the solution, according to Crime Tech Solutions’ CEO Doug Wood, is the

At the core of the solution, according to Crime Tech Solutions’ CEO Doug Wood, is the

Douglas Wood is President and CEO of Texas-based

Douglas Wood is President and CEO of Texas-based