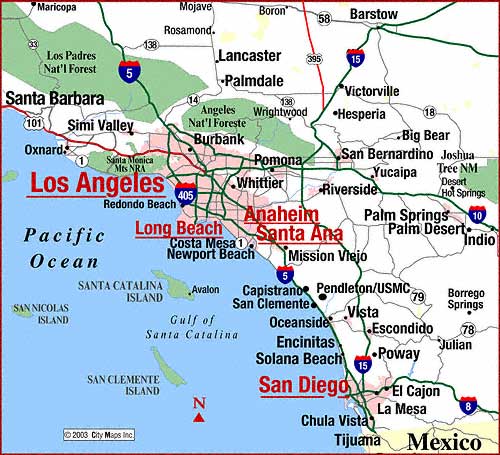

Crime Tech Solutions, LLC – a fast growing, vibrant software company based in Leander, TX today announced that a large, coastal city in California has selected them to provide sophisticated link and social network analysis software.

Crime Tech Solutions, LLC – a fast growing, vibrant software company based in Leander, TX today announced that a large, coastal city in California has selected them to provide sophisticated link and social network analysis software.

Crime Tech Solutions was awarded the contract based upon its price/performance leadership in the world of big data analytics for law enforcement and other investigative agencies.

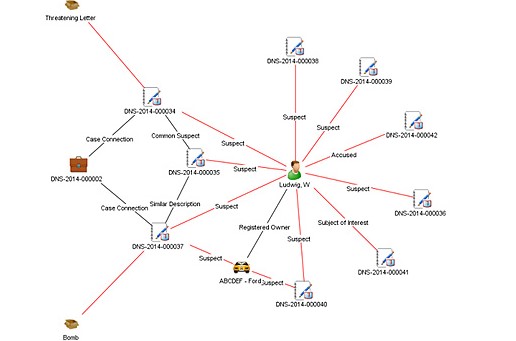

Link analysis software is used by investigators to visualize hidden connections between people, places, and things within large and disparate data sets.

“Our link analysis software gives investigators an edge in the way they analyze data”, said Crime Tech Solutions’ CEO, Doug Wood. “By finding and displaying those hard to find connections and anomalies that reside in different data stores, our software helps investigative agencies more clearly see how networks of entities exist.”

Crime Tech Solutions said that the software implementation is already underway, and that the software will make life a little more miserable for criminals in the Southern California city.

The company also develops investigative case management and criminal intelligence software for law enforcement agencies of all sizes.

Happy Father's Day to all the dads who serve!

Criminal Intelligence Management: Best Practices

Criminal intelligence analysts provide a key element of effective law enforcement, at both the tactical and strategic levels. Analysts study information related to suspects, trends, known criminals, and more. Through a process of gathering evaluating this information, trained intelligence analysts identify associations across various illegal activities over many locations.

Government decisions and policies are heavily influenced by the insights provided by the criminal intelligence analyst, and police investigations use the intelligence in support of their missions. To that end, the main functions of criminal intelligence analysts include:

Government decisions and policies are heavily influenced by the insights provided by the criminal intelligence analyst, and police investigations use the intelligence in support of their missions. To that end, the main functions of criminal intelligence analysts include:

- Supporting law enforcement activities and large-scale investigations

- Providing an ongoing analysis of potential threats to public safety

- Helping senior officials and policy makers to deal with ever-evolving challenges and uncertainty

There are both tactical and strategic elements to the role of the criminal intelligence analyst. These categories differ with respect to the minutia of details, and the ‘customer’ or end-user of the intelligence.

A. Tactical Criminal Intelligence

Criminal intelligence of a tactical nature attempts to achieve a specific outcome related to law enforcement. Perhaps a disruption of organized criminal groups, a search warrant, seizure of assets, or an arrest.

Tactical criminal intelligence includes:

- The identification of potential connections between people, places, and other entities of interest… and their potential involvement in unlawful activities;

- Recognizing and reporting important gaps in intelligence data;

- Designing and creating detailed dossiers of suspected or confirmed criminals.

B. Strategic Criminal Intelligence

B. Strategic Criminal Intelligence

Strategic analysis of criminal intelligence is expected to continuously educate policy makers and senior officials about current and evolving criminal activities and patterns. The benefits of strategic analysis tend to be realized over a longer period of time than does tactical analysis.

Emerging criminal trends and activities sit at the core of strategic intelligence analysis. The intelligence can provide advanced warning of potential threats, and can provide law enforcement officials with the information required to prepare their agencies for emerging illegal actions.

Strategic criminal intelligence analysis includes the recognition and documentation of:

- Evolving trends and patterns of illegal activities

- Developing threats

- Modus operandi

- The possible effect of demographics, technologies, and evolving socio-economic factors on criminal activities

D. Abuse and Misuse of Criminal Intelligence

D. Abuse and Misuse of Criminal Intelligence

The misuse and/or improper storage and unauthorized access to sensitive criminal intelligence data has always been a concern of civil liberty advocates, and has recently been brought to light again with stories regarding misuse of California’s CalGang database. Given the diverse and growing requirements of criminal intelligence management, certain best-practices and policies have evolved in order to help law enforcement agencies collect, store, and disseminate this important criminal intelligence without invading individual rights to privacy.

E. Best Practices for Criminal Intelligence Management

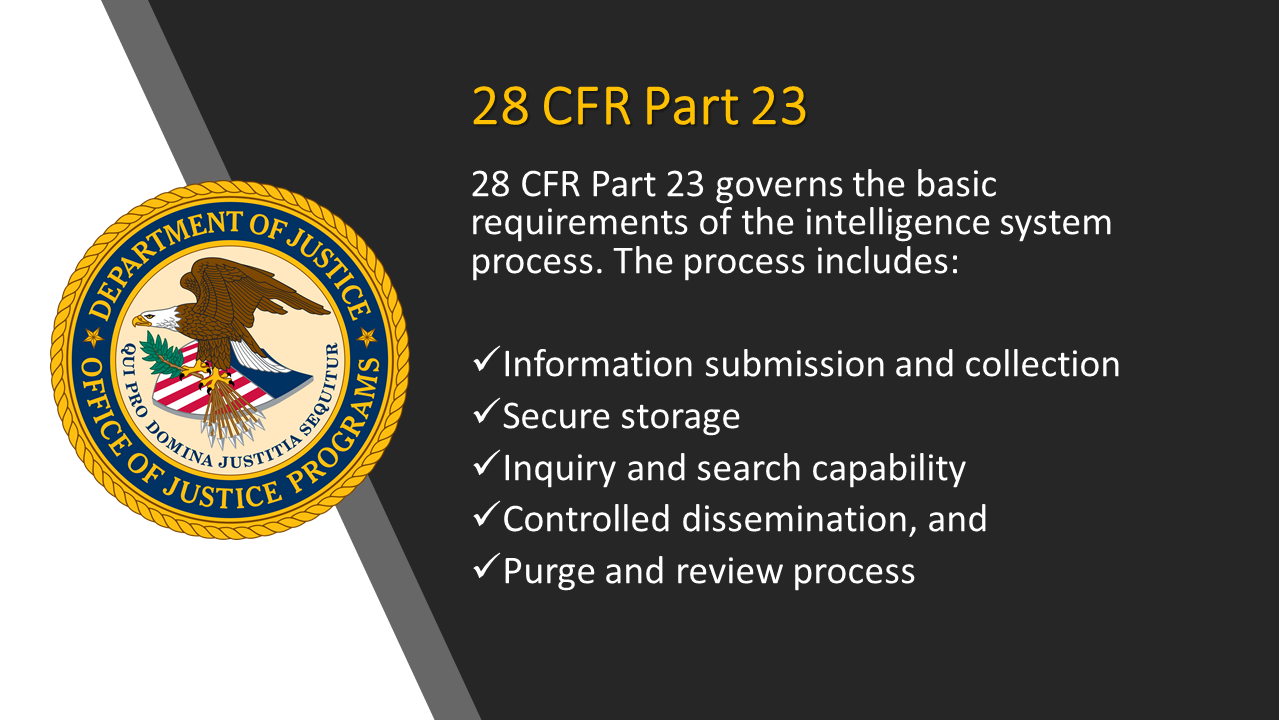

Specifically, 28 CFR Part 23 is a federal regulation that provides guidance to law enforcement agencies on the standards for implementing and operating federally funded criminal intelligence systems that cross jurisdictions. The protection of individual constitutional rights and civil liberties sits at the core of 28 CFR Part 23. Every American, of course, is afforded a reasonable expectation of privacy. The guidelines outline specific methods to gather, store, disseminate, review, and purge criminal intelligence data.

Specifically, 28 CFR Part 23 is a federal regulation that provides guidance to law enforcement agencies on the standards for implementing and operating federally funded criminal intelligence systems that cross jurisdictions. The protection of individual constitutional rights and civil liberties sits at the core of 28 CFR Part 23. Every American, of course, is afforded a reasonable expectation of privacy. The guidelines outline specific methods to gather, store, disseminate, review, and purge criminal intelligence data.

Recommending the use of these guidelines is The National Criminal Intelligence Sharing Plan (NCISP). NCISP suggests that the regulations ensure that the operations of a criminal intelligence system protect the rights and privacy of individuals and organizations. Importantly, The NCISP suggests that criminal intelligence groups adhere to 28 CFR Part 23, irrespective of whether or not the system was implemented using federal funds and grants.

The criminal intelligence guidelines prescribed by 28 CFR Part 23 have been identified as the minimal policies and rules for sharing data across law enforcement agencies.

The best practices prescribed within the regulation include specific guidelines related to:

- Proper procedures for querying, reviewing, sharing, validating, and purging of criminal intelligence data.

- Multi-jurisdictional memorandums and participation agreements (if applicable).

- The gathering and submission of criminal intelligence information.

- The definition of key criminal intelligence terminology, including ‘the right to know’ and ‘the need to know’.

- The specific activities that may or may not be maintained within the criminal intelligence system.

- Individual rights to access the criminal intelligence systems.

- Security requirements including the auditing and inspection of data.

F. An Excellent Solution

IntelNexus™ from software developer Crime Tech Solutions is an affordable, yet powerful criminal intelligence management system that complies with the regulations and best practices set forth in 28 CFR Part 23. Whether or not an agency (or agencies) absolutely require compliance to 28 CFR Part 23, the software lays out a framework and enforces the principles that should be incorporated into the criminal intelligence database. IntelNexus offers the foundation for gathering, storing, maintaining, sharing, authenticating, and purging criminal intelligence while ensuring the privacy and civil rights afforded to us all.

IntelNexus™ from software developer Crime Tech Solutions is an affordable, yet powerful criminal intelligence management system that complies with the regulations and best practices set forth in 28 CFR Part 23. Whether or not an agency (or agencies) absolutely require compliance to 28 CFR Part 23, the software lays out a framework and enforces the principles that should be incorporated into the criminal intelligence database. IntelNexus offers the foundation for gathering, storing, maintaining, sharing, authenticating, and purging criminal intelligence while ensuring the privacy and civil rights afforded to us all.

The company also develops the popular Case Closed™ investigation case management software, and provides a suite of advanced crime analytics and link analysis software.

Compliance with CFR 28 Part 23 Criminal Intelligence Systems Operating Policies

As a guide for those interested in criminal intelligence systems such as IntelNexus™, Crime Tech Weekly is publishing the following overview of Title 28, Part 23 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR 28 Part 23). The policy reads as follows:

CFR 28 PART 23–CRIMINAL INTELLIGENCE SYSTEMS OPERATING POLICIES

1. Purpose.

2. Background.

3. Applicability.

4. Operating principles.

5. Funding guidelines.

6. Monitoring and auditing of grants for the funding of intelligence systems.

1 Purpose.

The purpose of this regulation is to assure that all criminal intelligence systems operating through support under the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968 are utilized in conformance with the privacy and constitutional rights of individuals.

2 Background.

It is recognized that certain criminal activities including but not limited to loan sharking, drug trafficking, trafficking in stolen property, gambling, extortion, smuggling, bribery, and corruption of public officials often involve some degree of regular coordination and permanent organization involving a large number of participants over a broad geographical area. The exposure of such ongoing networks of criminal activity can be aided by the pooling of information about such activities. However, because the collection and exchange of intelligence data necessary to support control of serious criminal activity may represent potential threats to the privacy of individuals to whom such data relates, policy guidelines for Federally funded projects are required.

3 Applicability.

(a) These policy standards are applicable to all criminal intelligence systems operating through support under the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968.

(b) As used in these policies: Criminal Intelligence System or Intelligence System means the arrangements, equipment, facilities, and procedures used for the receipt, storage, interagency exchange or dissemination, and analysis of criminal intelligence information; Inter-jurisdictional Intelligence System means an intelligence system which involves two or more participating agencies representing different governmental units or jurisdictions; Criminal Intelligence Information means data which has been evaluated to determine that it: (i) is relevant to the identification of and the criminal activity engaged in by an individual who or organization which is reasonably suspected of involvement in criminal activity, and (ii) meets criminal intelligence system submission criteria; Participating Agency means an agency of local, county, State, Federal, or other governmental unit which exercises law enforcement or criminal investigation authority and which is authorized to submit and receive criminal intelligence information through an inter-jurisdictional intelligence system. A participating agency may be a member or a nonmember of an inter-jurisdictional intelligence system; Intelligence Project means the organizational unit which operates an intelligence system on behalf of and for the benefit of a single agency or the organization which operates an inter-jurisdictional intelligence system on behalf of a group of participating agencies; and Validation of Information means the procedures governing the periodic review of criminal intelligence information to assure its continuing compliance with system submission criteria established by regulation or program policy.

4 Operating principles.

4 Operating principles.

(a) A project shall collect and maintain criminal intelligence information concerning an

individual only if there is reasonable suspicion that the individual is involved in criminal conduct or activity and the information is relevant to that criminal conduct or activity.

(b) A project shall not collect or maintain criminal intelligence information about the political, religious or social views, associations, or activities of any individual or any group, association, corporation, business, partnership, or other organization unless such information directly relates to criminal conduct or activity and there is reasonable suspicion that the subject of the information is or may be involved in criminal conduct or activity.

(c) Reasonable Suspicion or Criminal Predicate is established when information exists which establishes sufficient facts to give a trained law enforcement or criminal investigative agency officer, investigator, or employee a basis to believe that there is a reasonable possibility that an individual or organization is involved in a definable criminal activity or enterprise. In an inter-jurisdictional intelligence system, the project is responsible for establishing the existence of reasonable suspicion of criminal activity either through examination of supporting information submitted by a participating agency or by delegation of this responsibility to a properly trained participating agency which is subject to routine inspection and audit procedures established by the project.

(d) A project shall not include in any criminal intelligence system information which has been obtained in violation of any applicable Federal, State, or local law or ordinance. In an inter-jurisdictional intelligence system, the project is responsible for establishing that no information is entered in violation of Federal, State, or local laws, either through examination of supporting information submitted by a participating agency or by delegation of this responsibility to a properly trained participating agency which is subject to routine inspection and audit procedures established by the project.

(e) A project or authorized recipient shall disseminate criminal intelligence information only where there is a need to know and a right to know the information in the performance of a law enforcement activity.

(f) (1) Except as noted in paragraph (f) (2) of this section, a project shall disseminate criminal intelligence information only to law enforcement authorities who shall agree to follow procedures regarding information receipt, maintenance, security, and dissemination which are consistent with these principles. (2) Paragraph (f) (1) of this section shall not limit the dissemination of an assessment of criminal intelligence information to a government official or to any other individual, when necessary, to avoid imminent danger to life or property.

(g) A project maintaining criminal intelligence information shall ensure that administrative, technical, and physical safeguards (including audit trails) are adopted to insure against unauthorized access and against intentional or unintentional damage. A record indicating who has been given information, the reason for release of the information, and the date of each dissemination outside the project shall be kept. Information shall be labeled to indicate levels of sensitivity, levels of confidence, and the identity of submitting agencies and control officials. Each project must establish written definitions for the need to know and right to know standards for dissemination to other agencies as provided in paragraph (e) of this section. The project is responsible for establishing the existence of an inquirer’s need to know and right to know the information being requested either through inquiry or by delegation of this responsibility to a properly trained participating agency which is subject to routine inspection and audit procedures established by the project. Each intelligence project shall assure that the following security requirements are implemented: (1) Where appropriate, projects must adopt effective and technologically advanced computer software and hardware designs to prevent unauthorized access to the information contained in the system; (2) The project must restrict access to its facilities, operating environment and documentation to organizations and personnel authorized by the project; (3) The project must store information in the system in a manner such that it cannot be modified, destroyed, accessed, or purged without authorization; (4) The project must institute procedures to protect criminal intelligence information from unauthorized access, theft, sabotage, fire, flood, or other natural or manmade disaster; (5) The project must promulgate rules and regulations based on good cause for implementing its authority to screen, reject for employment, transfer, or remove personnel authorized to have direct access to the system; and (6) A project may authorize and utilize remote (off-premises) system data bases to the extent that they comply with these security requirements.

(h) All projects shall adopt procedures to assure that all information which is retained by a project has relevancy and importance. Such procedures shall provide for the periodic review of information and the destruction of any information which is misleading, obsolete or otherwise unreliable and shall require that any recipient agencies be advised of such changes which involve errors or corrections. All information retained as a result of this review must reflect the name of the reviewer, date of review and explanation of decision to retain. Information retained in the system must be reviewed and validated for continuing compliance with system submission criteria before the expiration of its retention period, which in no event shall be longer than five (5) years.

(i) If funds awarded under the Act are used to support the operation of an intelligence system, then: (1) No project shall make direct remote terminal access to intelligence information available to system participants, except as specifically approved by the Office of Justice Programs (OJP) based on a determination that the system has adequate policies and procedures in place to insure that it is accessible only to authorized systems users; and (2) A project shall undertake no major modifications to system design without prior grantor agency approval.

(j) A project shall notify the grantor agency prior to initiation of formal information exchange procedures with any Federal, State, regional, or other information systems not indicated in the grant documents as initially approved at time of award.

(j) A project shall notify the grantor agency prior to initiation of formal information exchange procedures with any Federal, State, regional, or other information systems not indicated in the grant documents as initially approved at time of award.

(k) A project shall make assurances that there will be no purchase or use in the course of the project of any electronic, mechanical, or other device for surveillance purposes that is in violation of the provisions of the Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986, Public Law 99-508, 18 U.S.C. 2510-2520, 2701-2709 and 3121-3125, or any applicable State statute related to wiretapping and surveillance.

(l) A project shall make assurances that there will be no harassment or interference with any lawful political activities as part of the intelligence operation.

(m) A project shall adopt sanctions for unauthorized access, utilization, or disclosure of

information contained in the system.

(n) A participating agency of an inter-jurisdictional intelligence system must maintain in its agency files information which documents each submission to the system and supports compliance with project entry criteria. Participating agency files supporting system submissions must be made available for reasonable audit and inspection by project representatives. Project representatives will conduct participating agency inspection and audit in such a manner so as to protect the confidentiality and sensitivity of participating agency intelligence records.

(o) The Attorney General or designee may waive, in whole or in part, the applicability of a particular requirement or requirements contained in this part with respect to a criminal intelligence system, or for a class of submitters or users of such system, upon a clear and convincing showing that such waiver would enhance the collection, maintenance or dissemination of information in the criminal intelligence system, while ensuring that such system would not be utilized in violation of the privacy and constitutional rights of individuals or any applicable state or federal law.

5 Funding guidelines.

5 Funding guidelines.

The following funding guidelines shall apply to all Crime Control Act funded discretionary assistance awards and Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) formula grant program subgrants, a purpose of which is to support the operation of an intelligence system. Intelligence systems shall only be funded where a grantee/subgrantee agrees to adhere to the principles set forth above and the project meets the following criteria:

(a) The proposed collection and exchange of criminal intelligence information has been

coordinated with and will support ongoing or proposed investigatory or prosecutorial activities relating to specific areas of criminal activity.

(b) The areas of criminal activity for which intelligence information is to be utilized represent a significant and recognized threat to the population and: (1) Are either undertaken for the purpose of seeking illegal power or profits or pose a threat to the life and property of citizens; and (2) Involve a significant degree of permanent criminal organization; or (3) Are not limited to one jurisdiction.

(c) The head of a government agency or an individual with general policy making authority who has been expressly delegated such control and supervision by the head of the agency will retain control and supervision of information collection and dissemination for the criminal intelligence system. This official shall certify in writing that he or she takes full responsibility and will be accountable for the information maintained by and disseminated from the system and that the operation of the system will be in compliance with the principles set forth in 23.20.

(d) Where the system is an inter-jurisdictional criminal intelligence system, the governmental agency which exercises control and supervision over the operation of the system shall require that the head of that agency or an individual with general policymaking authority who has been expressly delegated such control and supervision by the head of the agency: (1) assume official responsibility and accountability for actions taken in the name of the joint entity, and (2) certify in writing that the official takes full responsibility and will be accountable for insuring that the information transmitted to the inter-jurisdictional system or to participating agencies will be in compliance with the principles set forth in 23.20. The principles set forth in 0 23.20 shall be made part of the by-laws or operating procedures for that system. Each participating agency, as a condition of participation, must accept in writing those principles which govern the submission, maintenance and dissemination of information included as part of the inter-jurisdictional system.

(e) Intelligence information will be collected, maintained and disseminated primarily for State and local law enforcement efforts, including efforts involving Federal participation.

6 Monitoring and auditing of grants for the funding of intelligence systems.

(a) Awards for the funding of intelligence systems will receive specialized monitoring and audit in accordance with a plan designed to insure compliance with operating principles as set forth in 23.20. The plan shall be approved prior to award of funds.

(b) All such awards shall be subject to a special condition requiring compliance with the

principles set forth in 23.20.

(c) An annual notice will be published by OJP which will indicate the existence and the objective of all systems for the continuing inter-jurisdictional exchange of criminal intelligence information which are subject to the 28 CFR Part 23 Criminal Intelligence Systems Policies.

___________

Crime Tech Solutions is a leading provider of criminal intelligence database management software for 28 CFR Part 23 compliance. The company also develops Case Closed™ investigation case management software, sophisticated link analysis software, and advanced crime analytics.

Crime Tech Solutions is a leading provider of criminal intelligence database management software for 28 CFR Part 23 compliance. The company also develops Case Closed™ investigation case management software, sophisticated link analysis software, and advanced crime analytics.

Criminal Intelligence Databases: Violations of privacy rights are the exception, not the rule.

The notion that law enforcement fusion centers regularly violate individuals’ privacy rights as they capture intelligence on gangs, terrorist activities, organized crime, and other threats to public safety is simply not true. That, according to a study published in the Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology.

The notion that law enforcement fusion centers regularly violate individuals’ privacy rights as they capture intelligence on gangs, terrorist activities, organized crime, and other threats to public safety is simply not true. That, according to a study published in the Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology.The paper, “Law Enforcement Fusion Centers: Cultivating an Information Sharing Environment while Safeguarding Privacy,” was authored by Jeremy Carter, an assistant professor of Public and Environmental Affairs at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis. His article carefully addresses the privacy-rights issue of criminal intelligence gathering, among others.

There are approximately 80 fusion centers in the United States. They were created in response to the 9/11 terrorist attacks. The attacks exposed the requirement for greater information sharing and improved intelligence capabilities at all law enforcement levels. According to the article’s author, the idea was to have the key pieces of data funneled into fusion centers so that highly trained analysts could stay atop of threats and correspond with local law enforcement agencies on these potential threats.

There are approximately 80 fusion centers in the United States. They were created in response to the 9/11 terrorist attacks. The attacks exposed the requirement for greater information sharing and improved intelligence capabilities at all law enforcement levels. According to the article’s author, the idea was to have the key pieces of data funneled into fusion centers so that highly trained analysts could stay atop of threats and correspond with local law enforcement agencies on these potential threats.Designed with a view to enhance information-sharing among agencies, fusion centers act as ‘hubs’ of data and intelligence on gang activities, terrorist cells, organized crime, and other public safety threats. Vast amounts have data has been collected, and concerns about individual privacy and civil rights have ensued. The very legitimacy of these fusion centers has been called into question.

The notion that law enforcement fusion centers represent ‘Big Brother’, and that data is being stored and disseminated about people irrespective of whether they are suspected of criminal activity is simply wrong, according to Professor Carter.

The notion that law enforcement fusion centers represent ‘Big Brother’, and that data is being stored and disseminated about people irrespective of whether they are suspected of criminal activity is simply wrong, according to Professor Carter.Still, concerns remain about who can access the data, and for what purpose. However, a survey of fusion centers across the country suggests that they take appropriate steps to safeguard individual privacy via something called Federal Regulatory Code CFR 28 Part 23.

“Fusion centers are following the federal regulatory code, 28 CFR Part 23, that is the legal standard for collecting information,” Carter said. “That code says you have to establish a criminal predicate, basically probable cause, to keep information on identifiable individuals.”

“Fusion centers are following the federal regulatory code, 28 CFR Part 23, that is the legal standard for collecting information,” Carter said. “That code says you have to establish a criminal predicate, basically probable cause, to keep information on identifiable individuals.”Additionally, the majority of the fusion centers have implemented strong controls that provide built-in safeguards that protect the privacy of individuals. The fusion centers are also regularly audited to ensure that only the correct type of data is gathered, and that is stored and disseminated in a need-to-know basis.

Crime Tech Solutions develops and markets a suite of crime fighting software including IntelNexus™, a criminal intelligence database system that complies with the above mentioned code 28 CFR Part 23. The company also provides software for investigation case management, advanced crime analytics, and link/social network analysis.

Crime Tech Solutions develops and markets a suite of crime fighting software including IntelNexus™, a criminal intelligence database system that complies with the above mentioned code 28 CFR Part 23. The company also provides software for investigation case management, advanced crime analytics, and link/social network analysis.

Gang Database leads to Arrest

El Paso, TX – Gang investigators were told a suspect in surveillance footage matched the description of “Flaco”, a known gang member in the area.

A search of a gang database identified “Flaco” as 32 year old Fidel Trevino, a court document states.

See the original story HERE at kvia.com

Crime Tech Solutions develops and markets the industry leading GangBuster™ gang tracking software for law enforcement. The company offers a suite of crime-fighting software including case management, link analysis, criminal intelligence management, and advanced crime analytics.

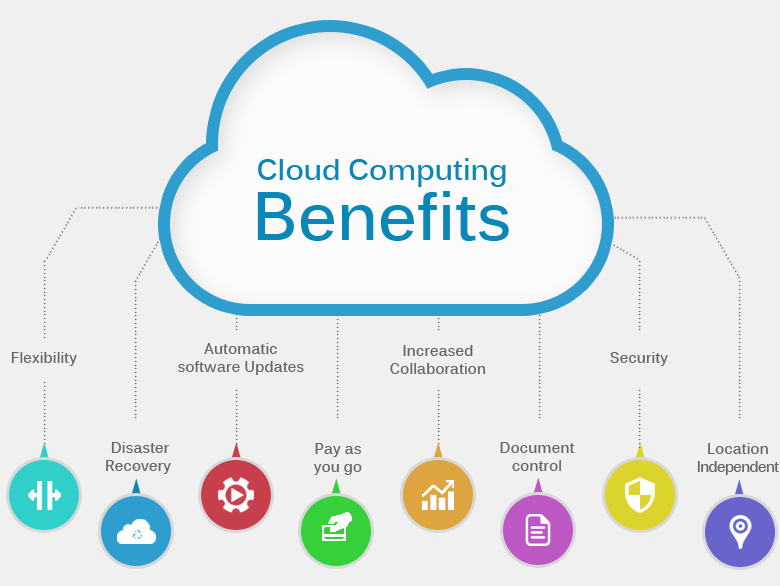

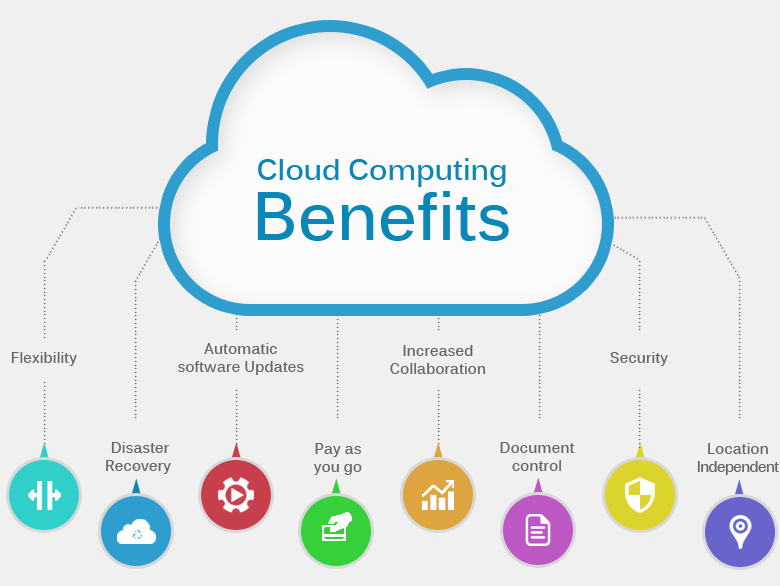

The Sunny Side of Cloud-Based Solutions

Cloud computing for law enforcement, in simple terms, refers to software hosted off-agency and available to the user through their internet connection. This type of software-as-a-service, or “SaaS” offers several advantages over software that is hosted locally on the user’s hardware.

Cloud computing for law enforcement, in simple terms, refers to software hosted off-agency and available to the user through their internet connection. This type of software-as-a-service, or “SaaS” offers several advantages over software that is hosted locally on the user’s hardware.

Computer hardware is always being tweaked and improved upon, and state-of-the-art equipment can become obsolete extremely quickly in this environment. Many vital pieces of software that law enforcement rely on can be extremely demanding of hardware resources. With cloud-based software solutions, the software and the hardware required to run it are maintained offsite. The agency users simply access the software through an internet browser on a computer or smart phone, and have access to all the functionality of the software with none of the costs or hassle involved in hosting locally. These costs also include maintenance and security.

Cloud-based solutions such as Case Closed Cloud also allow for software to be more portable, as the software can be easily and readily accessed by any user with a smart phone. In addition, compatibility across platforms becomes less of an issue, as the software only needs an internet browser to function. This means law enforcement officials can seamlessly move from using a MacBook at work, to their Windows Phone at lunch, to a Linux based PC at home, without having three separate installs with varying functionality.

There are some things to look out for. While having software and hardware off-site offers great advantages, it’s important to note that data is hosted off-site as well. It’s important to carefully navigate the terms of use and make certain that the agency is not signing away the rights to important, classified, or proprietary data.

There are some things to look out for. While having software and hardware off-site offers great advantages, it’s important to note that data is hosted off-site as well. It’s important to carefully navigate the terms of use and make certain that the agency is not signing away the rights to important, classified, or proprietary data.

Still, the major advantages of cloud-based software make it a powerful and very accessible tool for law enforcement. The simplicity and ease of access are defining characteristics of the cloud-based revolution.

The Case for Software as a Service in Law Enforcement

State and local law enforcement agencies face a growing number of challenges due to lack of resources and the ever-dwindling public coffers. As a result of legacy technologies that compound costs – through maintenance fees, implementation expenses, hardware purchases, and software upgrades – agencies are constantly challenged to do more with less.

State and local law enforcement agencies face a growing number of challenges due to lack of resources and the ever-dwindling public coffers. As a result of legacy technologies that compound costs – through maintenance fees, implementation expenses, hardware purchases, and software upgrades – agencies are constantly challenged to do more with less.

To reduce cost and increase flexibility, more and more law enforcement departments are motivated to try cloud computing- Software as a service (SaaS). The benefits of SaaS to law enforcement agencies are many and varied.

Reduced Investment in Software Setup

The majority of the law enforcement organizations already have the needed IT infrastructure to access SaaS applications. The essential requirement is a secure and stable Internet connection with devices that can access the web.

The majority of the law enforcement organizations already have the needed IT infrastructure to access SaaS applications. The essential requirement is a secure and stable Internet connection with devices that can access the web.

Cloud Computing Lessens Technical Effort

With SaaS solutions, agencies can easily store data or run applications which are accessible from any web-connected device at anywhere and anytime. Instead of investing in capital expenses such as software and computer servers, departments can effectively rent these on a variable payment plan.

Rapid Deployment

SaaS is typically ready-baked for its adopters. Through SaaS, agencies eliminate much of the delays of a traditional software deployment. Once subscribed, users can literally begin enjoying the benefit of the platform immediately. Contrast that to standard software deployments which can take weeks or months to spin up.

System Maintenance is Automatic

Maintenance costs for SaaS subscribers are almost free. As part of their subscription fee, the SaaS provider manages upgrades, bandwidth adjustment, and bug fixes. It removes many of the headaches that an agency’s IT group experiences with new software versions and updates.

Traditional Policies Can Confound Adoption

Even though many US agencies are already using – or considering – cloud computing, adoption of SaaS is still a tricky decision for law enforcement. Because of the need to safeguard sensitive and confidential information that is saved offsite, the pace is slower than other market segments. That tide, however, is turning.

Case Closed Software is a leading provider of investigative case management software for law enforcement agencies across the country.

Tennessee county turns to Case Closed for investigation management

(March 27, 2017) Case Closed™ Software, a division of crime fighting software leader Crime Tech Solutions, LLC, announced today that they have signed contract with a large well-known and historic county in Tennessee.

The mid-sized Sheriff’s Department in the Volunteer State chose Case Closed Software after a long, thorough search for a solution provider capable of delivering “a feature-rich, affordable solution for managing investigations and the investigative unit”. The core modules of the software include Investigative Case Management, Link Analysis, Confidential Informants Management, Property & Evidence, Gang Tracking, and Departmental Reporting. According to a company spokesperson, the software also includes a mobile application for investigators in the field, and real-time alerting designed to help agencies solve crimes faster.

The mid-sized Sheriff’s Department in the Volunteer State chose Case Closed Software after a long, thorough search for a solution provider capable of delivering “a feature-rich, affordable solution for managing investigations and the investigative unit”. The core modules of the software include Investigative Case Management, Link Analysis, Confidential Informants Management, Property & Evidence, Gang Tracking, and Departmental Reporting. According to a company spokesperson, the software also includes a mobile application for investigators in the field, and real-time alerting designed to help agencies solve crimes faster.

Case Closed Software said that the solution is being installed immediately, and that the agency will be fully implemented by April 30, 2017.

For more information on Case Closed, visit www.caseclosedsoftware.com

UK Intelligence Training Provider Selects Crime Tech Solutions

February 24, 2017 – Austin, TX Crime Tech Solutions, a fast-growing software company in Leander, TX today announced that a large, England based intelligence training organization has standardized on the their powerful link analysis software for all ongoing end-user training.

Under the terms of the agreement, Crime Tech Solutions will provide the core link analysis software that will be used to train intelligence analysts across the United Kingdom.

Under the terms of the agreement, Crime Tech Solutions will provide the core link analysis software that will be used to train intelligence analysts across the United Kingdom.

Crime Tech Solutions is an innovator in crime analytics and law enforcement crime-fighting software. The clear price/performance leader for crime fighting software, the company’s offerings also include sophisticated Case Closed™ investigative case management and major case management, GangBuster™ gang intelligence software, powerful link analysis software, evidence management, mobile applications for law enforcement, comprehensive crime analytics with mapping and predictive policing, and 28 CFR Part 23 compliant criminal intelligence database management systems.