Posted by Douglas Wood, CEO of Case Closed Software – a leader in investigation software and analytics for law enforcement.

Headquartered here in Central Texas, I recently had an opportunity to have coffee with Dr. Sarah Brayne, Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology at The University of Texas at Austin. Ms. Brayne had just published an interesting article in The American Sociological Review. The article is titled Big Data Surveillance: The Case of Policing.

The article examines the intersection of two emerging developments: the increase in surveillance and the massive exploration of “big data.” Drawing on observations and interviews conducted within the Los Angeles Police Department, Sarah offers an empirical account of how the adoption of big data analytics does—and does not—transform police surveillance practices.

She argues that the adoption of big data analytics facilitates may amplify previous surveillance practices, and outlines the following findings:

- Discretionary assessments of risk are supplemented and quantified using risk scores.

- Data tends to be used for predictive, rather than reactive or explanatory, purposes. (Here, Crime Tech Weekly would want to differentiate between predictive analytics and investigation analytics)

- The proliferation of automatic alert systems makes it possible to systematically surveil an unprecedentedly large number of people.

- The threshold for inclusion in law enforcement databases (gang databases, criminal intelligence data, etc) is lower, now including individuals who have not had direct police contact. (Here again, Crime Tech Weekly would point out that adherence to criminal intelligence best practices vastly reduces this likelihood)

- Previously separate data systems are merged, facilitating the spread of surveillance into a wide range of institutions.

Based on these findings, Sarah develops a theoretical model of big data surveillance that can be applied to institutional domains beyond the criminal justice system. Finally, she highlights the social consequences of big data surveillance for law and social inequality.

The full PDF report can be downloaded via Sage Publishing by clicking here. Or, if you have general comments or questions and do not wish to download the full version, please feel free to contact us through the form below. Crime Tech Weekly will be happy to weigh in.

[contact-form][contact-field label=”Name” type=”name” required=”1″ /][contact-field label=”Email” type=”email” required=”1″ /][contact-field label=”Website” type=”url” /][contact-field label=”Comment” type=”textarea” required=”1″ /][/contact-form]

A recent report questions how some police departments are using data to forecast future crimes.

A recent report questions how some police departments are using data to forecast future crimes. How police departments nationwide utilize crime statistics and the software available to patrol officers monitoring incidents has evolved a lot in the past couple decades, Sgt. Tracy Barton with the St. Joseph Police Department said. Barton started as a patrol officer 20 years ago. He said having software like police have today would have been useful.

How police departments nationwide utilize crime statistics and the software available to patrol officers monitoring incidents has evolved a lot in the past couple decades, Sgt. Tracy Barton with the St. Joseph Police Department said. Barton started as a patrol officer 20 years ago. He said having software like police have today would have been useful.

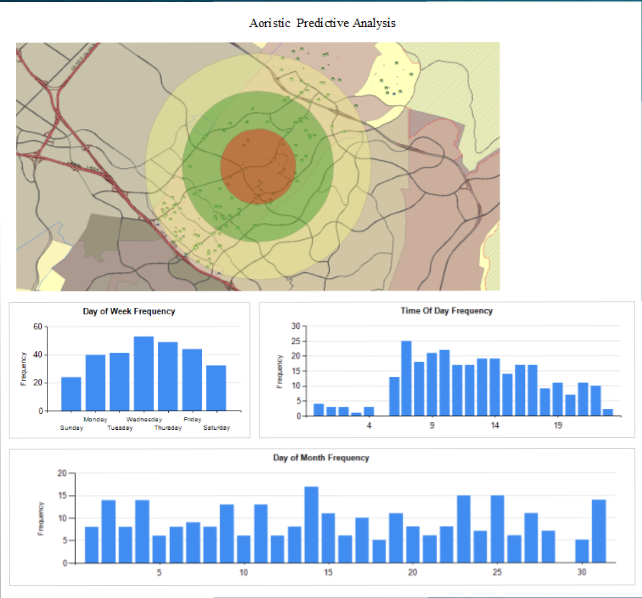

ryant worked with the Shawnee, Kansas, Police Department on research that looked at what he calls “smart policing.” In his research and in other work he has read, Bryant said it’s important for police to have a high visibility in crime hot spots, for officers to make connections with the public and for them to avoid staying in crime hot spots for extended periods of time.

ryant worked with the Shawnee, Kansas, Police Department on research that looked at what he calls “smart policing.” In his research and in other work he has read, Bryant said it’s important for police to have a high visibility in crime hot spots, for officers to make connections with the public and for them to avoid staying in crime hot spots for extended periods of time.

Advocates say ‘Great, let’s prevent the crime from happening’. Opponents say ‘The output is only as good as the input’. In other words, there are claims that a reliance upon historical data unduly influences the prediction. The position suggests that if police have tended to make arrests in Location A, then of course predictive policing will suggest patrolling Location A.

Advocates say ‘Great, let’s prevent the crime from happening’. Opponents say ‘The output is only as good as the input’. In other words, there are claims that a reliance upon historical data unduly influences the prediction. The position suggests that if police have tended to make arrests in Location A, then of course predictive policing will suggest patrolling Location A.