Case Closed Software™ recently worked on a project with the City of San Diego Police Department’s Internet Crimes Against Children (ICAC) Task Force.

The project arose out of a need for a sophisticated tool to help the multi-jurisdictional ICAC unit effectively triage and investigate criminal activity involving child sexual abuse materials (CSAM). In particular, we needed to come up with an investigation tool that would work around evolving laws and The Wilson Ruling of 2021.

Note: CSAM has previously been referred to as ‘Child Pornography’, but has evolved into a more accurate depiction of the abuse committed upon unwilling victims.

At the root of Wilson Ruling, which we will discuss in depth below, is the 2008 Protect Our Children Act sponsored by then-Senator Joe Biden and signed by then-President George W. Bush. The law requires “electronic communication service providers to notify the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC) when they discover apparent violations of laws prohibiting CSAM.

NCMEC then creates and distributes CyberTips to appropriate law enforcement agencies and specially-trained agents.

NCMEC then creates and distributes CyberTips to appropriate law enforcement agencies and specially-trained agents.

The Anatomy of a NCMEC CyberTip for ICAC Units

Without getting too granular, a CyberTip is made up of several sections. There’s a front page, and Sections A through D. The front page will contain the date it was received, its assigned report number, and an executive summary. The executive summary will say what type of incident the report refers to, such as “Apparent Child Pornography”, and the number of files that were uploaded.

The first section of a CyberTip, Section A, has information about the reporting agency – Google, Facebook, TikTok and so on. It will also include a brief incident description, the time of the incident, the webpage involved, and the email, username, and IP address of the person reported.

Spoiler Alert… Here’s a key to The Wilson Ruling: For each file, this section says whether the reporting ESP actually viewed the file and whether the file was publicly available. We’re going to come back to this shortly.

Section B is geolocation information for the offending IP address given in the report. This helps NCMEC know which ICAC Task Force should get the tip. The ISP who owns or controls the IP address will also be listed.

Section C is for any additional information and may reference other CyberTips that are associated with the same username or IP address.

Here’s another key point related to The Wilson Ruling. The images or videos associated with the CyberTip are provided to the appropriate agency along with a PDF report, but they are NOT shown in the body of the report.

Why the CyberTip Matters

The point of describing the CyberTip here is to reinforce just how much unstructured data exists on them and foreshadow some of the pain points that ICAC teams experience in getting these CyberTips triaged.

That’s a significant component of the partnership that Case Closed Software has developed with San Diego Police Department… how to manage, de-conflict, and triage the overwhelming volume of CyberTips that each ICAC task force or investigator receives.

That’s a significant component of the partnership that Case Closed Software has developed with San Diego Police Department… how to manage, de-conflict, and triage the overwhelming volume of CyberTips that each ICAC task force or investigator receives.

The other significant component of what we’ve worked on together from a technology perspective is related to how courts have applied Fourth Amendment doctrines to CSAM investigations. The Fourth Amendment, of course, is an important piece of our Bill of Rights and is supposed to protect all of us from unreasonable searches and seizures by the government.

The ICAC Investigation into Luke Noel Wilson

Let’s look at The Wilson Ruling of 2021. This came out of the court’s application of the Fourth Amendment in the case of defendant Luke Noel Wilson who, in June 2015, attached several images containing CSAM to an email on his Gmail account. Google’s screening system – which scans uploaded images and checks for identical matches in a database of confirmed CSAM – immediately flagged Wilson’s attachments as “apparent child pornography”.

Without having an employee review the attachments first, Google’s system then sent an automated report to NCMEC that included the images. As is standard policy for ESPs, the report contained information about the date and time Wilson uploaded the images, along with his email address, login information, and the IP address of the device he used to upload the images.

NCMEC subsequently forwarded the report to local law enforcement – in this case, the fine team at San Diego ICAC – where an agent reviewed the NCMEC CyberTip and inspected each of the images, confirming that they were indeed CSAM.

Relying on Google’s report and his personal observations, the agent then applied for – and obtained – a search warrant for Wilson’s email account. The agent’s affidavit accompanying the search warrant request included descriptions of the images but didn’t specifically contain any mention of matching hash values, nor any description of Google’s screening process for CSAM.

When, with search warrant in hand, the agent searched Wilson’s email account, he discovered several email exchanges in which Wilson received and sent CSAM and additionally offered to pay a woman to molest and exploit children.

Law Enforcement then obtained a search warrant for Wilson’s residence and vehicle where they discovered devices containing thousands of images of CSAM including the original four attachments. Wilson’s alleged attempt at throwing a backpack over his balcony was noticed by assisting agents and was found to contain a thumb drive full of additional Child Sexual Abuse Materials.

It was later estimated that Wilson possessed 500 videos and 11,000 images of child sexual abuse, and – a few months later – he was arrested and charged with Distribution and Possession of Child Sexual Abuse Materials.

Wilson was convicted and sentenced to 45 years in prison.

So, this seems at this point like a fairly standard ICAC case. What then happened that fundamentally changed the way ICAC units operated to triage and investigate CyberTips?

The Motion to Suppress

After his trial, Wilson filed a motion to suppress the four original attachments (the ones included in the original CyberTip) AND all evidence subsequently seized from his email account and residence, arguing that San Diego ICAC’s initial review of his attachments was a warrantless search in violation of the Fourth Amendment.

After his trial, Wilson filed a motion to suppress the four original attachments (the ones included in the original CyberTip) AND all evidence subsequently seized from his email account and residence, arguing that San Diego ICAC’s initial review of his attachments was a warrantless search in violation of the Fourth Amendment.

The District Court denied his motion, however, reasoning that the government does not perform a ‘search’ within the context of the Fourth Amendment when it inspects something that is ‘virtually certain’ to contain contraband.

Wilson subsequently appealed that decision to The Ninth Circuit which reversed the lower court’s decision, concluding that the agent’s viewing of the attachments violated Wilson’s 4th Amendment rights and rejecting the position that there was ‘virtual certainty’.

Basically, the Ninth Circuit said that Google’s initial report specified only the ‘general’ age of the child and the ‘general’ nature of the acts shown, and had not been viewed by any Google employee.

Basically, the Ninth Circuit said that Google’s initial report specified only the ‘general’ age of the child and the ‘general’ nature of the acts shown, and had not been viewed by any Google employee.

By viewing the four attachments without a search warrant, therefore, the higher court concluded that law enforcement unlawfully obtained new, critical information, and then used that new information to obtain warrants to search Wilson’s home and email account.

Of key importance in the ruling was the assessment that, even though Google employees viewed images identical to Wilson’s to create Google’s database of suspected CSAM, they had not viewed the actual image itself.

By contrast, after viewing the images, law enforcement could describe “the number of minors depicted, their identity, the number of adults depicted alongside the minors, the setting, and the actual sexual acts depicted.” So, even though Google’s algorithm had flagged Wilson’s attachments to a mathematical certainty that his images were “bit-for-bit” duplicates of images identified by its employees as CSAM within their database, Wilson’s motion to suppress was granted.

The Fallout

The fallout for ICAC Task Forces has been tremendous because of this ruling. How are ICAC units and their respective affiliates, supposed to expeditiously review, triage, and investigate a massive and growing number of CyberTips while tip-toeing around an individual’s 4th Amendment rights?

Last year, San Diego ICAC approached Case Closed Software™ with this exact set of problems and we began work on a tool designed to systematically process CyberTips – one that automates what is currently a time-consuming chain of events.

The Trouble with Triage

For most ICAC Units, individual CyberTips must be downloaded as zip files via NCMEC or IDS. Those zip files contain PDF files with unstructured text that lists:

• Reporting Agencies

• Usernames

• Email Addresses

• Telephone Numbers

• IP Addresses

• Hash Values

• Physical Addresses

• Sender IDs

• Recipient IDs

• Suspect Names

• Victim Names

• … and much more.

Triage administrators must:

- Download each CyberTip locally

- Unzip the file

- Begin a long process of putting those data elements together to create a connected view of those data elements to determine solvability

- And then assign to an investigator – internal or affiliate.

Oh, and then do the same for the next CyberTip… and the next one… and the next one after that.

Problem Solving for ICAC

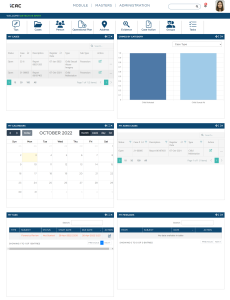

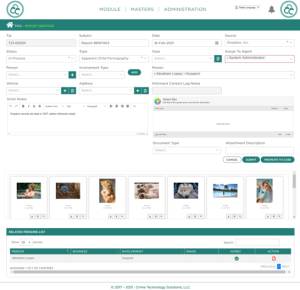

Working with San Diego ICAC, we created a tool that allows administrators to save CyberTips directly a CJIS-Compliant ‘black box’ server instead of downloading them locally. That black box contains proprietary logic that systematically opens those zip files, pulls all of those data elements from the PDFs, grabs all of the attachments and underlying hash values, and links them into a single interface for the administrator. Important to note is that this process happens quickly and virtually eliminates the manual efforts in existence now.

We have essentially created a unique, user-friendly system where investigators cannot view attachments until they purposely elect to.

They can see usernames, IP Addresses, filenames, and an array of other information… but not the images. Images cannot be revealed until investigators have proper authority in compliance of the Wilson Ruling. It’s a simple but brilliant addition to the process that protects all parties.

Just to tie a bow around Mr. Wilson, he was eventually convicted of child molestation on the Stateside and sentenced to 25 years. He was subsequently charged and convicted of possession and distribution of CSAM on the federal side and received an additional ten years. He is where he should be, but his entire case was thrown into jeopardy when one agent viewed four files that one court felt violated his rights.

The Proposed Solution: Case Closed Software™

At its core, Case Closed Software is a multi-jurisdictional investigation case management system for complex criminal investigations.

The ICAC-specific functionality that was added to the system takes what was once a CyberTip and, using what we call our ‘One Page Case Management’ methodology, helps turn it into a conviction.

Government decisions and policies are heavily influenced by the insights provided by the criminal intelligence analyst, and police investigations use the intelligence in support of their missions. To that end, the main functions of criminal intelligence analysts include:

Government decisions and policies are heavily influenced by the insights provided by the criminal intelligence analyst, and police investigations use the intelligence in support of their missions. To that end, the main functions of criminal intelligence analysts include:  B. Strategic Criminal Intelligence

B. Strategic Criminal Intelligence D. Abuse and Misuse of Criminal Intelligence

D. Abuse and Misuse of Criminal Intelligence Specifically,

Specifically,